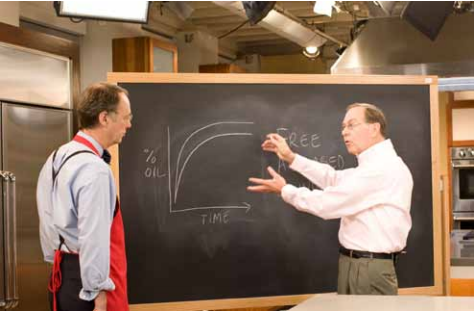

What makes for a chewier cookie? Why is this black-bean soup not blacker? Guy Crosby sifts through questions like these daily. He is the science editor at America’s Test Kitchen, the company that produces Cook’s Illustrated magazine and America’s Test Kitchen TV show. Crosby works to perfect not only the quality of science communication but the quality of food.

America’s Test Kitchen is based near Boston in a real kitchen the size of a generous four-bedroom apartment. There, dozens of cooks and food testers fine-tune classic recipes, tweaking the techniques and ingredients up to 70 times. The finished recipes are then prepared by a legion of volunteer home cooks. Only after being approved by the vast majority of volunteers can a recipe be published or appear on television.

When a recipe does not behave ideally, the professional cooks often turn for advice to Crosby, who has a doctorate in organic chemistry and more than 30 years of experience in food science.

Crosby came to America’s Test Kitchen about 5 years ago. For many years before that, he worked in the food industry, developing, among other things, food additives that act as dietary fiber. He then retired to consulting, writing, and lecturing. Aided by recipes from Cook’s Illustrated, he rediscovered his graduate-student cooking habit. Crosby was so impressed with Cook’s Illustrated that he wrote the founder, Christopher Kimball, offering his services as a food-science consultant.

A year later, Crosby received a call from America’s Test Kitchen Editorial Director Jack Bishop, asking whether he could recommend someone to work as a science editor for the company. “Maybe I’d be interested,” Crosby said.

To test Crosby’s skills, the editors of America’s Test Kitchen asked him to cook up a food-related experiment, analyze the results, and write a summary accessible to the general public. He picked an experiment that pertains to peaches’ ripening faster in a brown paper bag. Peaches, like some other fruits, produce ethylene gas and ripen in response to its presence. The brown paper bag traps and concentrates the ethylene coming from the peaches. Bananas produce lots of ethylene; to ripen peaches in a couple of days, one can simply place unripe peaches in a bag with bananas.

Crosby compared peaches ripened by placement in a paper bag, in a bag with bananas, and in a bowl. He basted peach slices with an iodide solution that turns purple on contact with starch. Whereas the starch in unripe peaches bloomed with purple, ripe peach slices colored little, because most of their starch had already turned to sugar. He had everyone test ripeness by taste as well.

“They photographed everything, then said, ‘let’s give it a try,’” Crosby says. “I’ve been going for 5 years.”

These days, Crosby’s job has expanded.

Unlike some other food magazines, which include articles on travel and entertaining and profile famous chefs, Cook’s Illustrated offers only recipes prepared in home kitchens, says America’s Test Kitchen’s Bishop.

“Our motto is ‘recipes that work’. To construct and prepare recipes that work, you have to know something about science,” Bishop says. “From the beginning, success in the kitchen depends on understanding the science.”

Crosby began by editing for accuracy and readability all the scientific explanations that pepper the recipes. He still does that, but the test cooks have found that he can also suggest ways to whip stubborn recipes into shape. For instance, what to do to keep the apples in apple pie from sometimes turning to mush? Try using fresh, locally grown apples. The mush-producing ones were probably picked when unripe and then spent too long in climate-controlled storage, which caused them to ripen quickly once brought home and to become mushy when cooked.

Crosby also helps to design more complicated ingredient tests that are sent off to laboratories—measuring the protein content in flour, for instance—and then helps to analyze data. To top it all off, he started prepping for and appearing on segments in America’s Test Kitchen TV. He never planned for this kind of postretirement career, he says.

A major perk of the job is volunteering to test the recipes, Crosby says. His own collection of favorite recipes consists of notes incomprehensible to anyone other than him and his wife, who also loves to cook.

On the side, Crosby teaches food science and chemistry courses at the Harvard School of Public Health and at Framingham State College. Food science is relatively young, he says. For most of its history, food scientists have collaborated with farmers to improve the quantity and safety of crops. As time has gone by, more food scientists have focused on improving the quality of food, Crosby says. He was offended a couple of years ago when a letter published in edible Boston claimed that all food scientists are simply looking for new ways to inject high-fructose corn syrup into foods. “If anybody understands the problems of growing local foods and appreciates them as much as or more than other people, it’s food scientists,” Crosby says.

In daily e-mails from America’s Test Kitchen staff, Crosby gets to solve a different set of problems. “Some of the facts are well known, some questions are impossible to answer at this time,” he says. “I look forward to getting new questions every day.”

Olga Kuchment, a former Science Editor intern, is a student in the science communication program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.