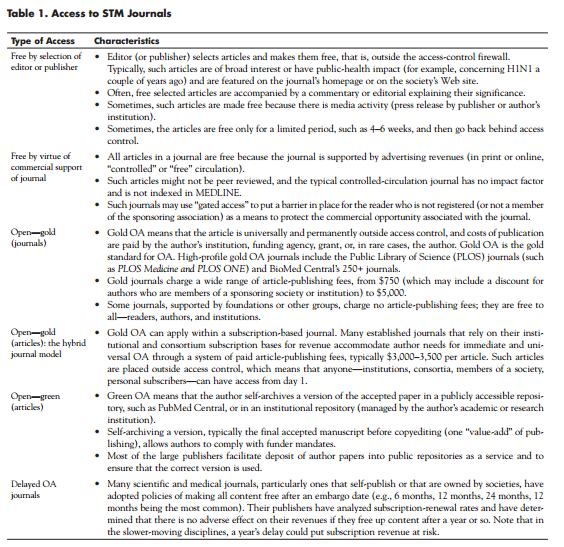

Open access (OA) is a term that—despite careful definition, intense discussion, and inherent significance for the scholarly publishing world—continues to be misused and misinterpreted. During the course of one recent meeting of the publications committee of a highly respected medical group, I heard OA referred to as “vanity publishing”, used interchangeably with “online-only” journals, and accused of being represented by no journal with “an impact factor greater than 2”! I imagine that my colleagues in CSE are a great deal more au courant than that group of doctors, but it does seem that OA has had its share of misconception. This article attempts to clarify the types of access that journals offer and the current status of OA journals.

The impetus for the OA movement was the idea that the results of research funded by taxpayers should be free to taxpayers, but the movement struck a chord with institutions as a way of combating their perennial budget constraints. The recession of 2009–2010 fueled an institutional desire for alternatives to subscription-based journals. Authors themselves have been under pressure or constraint by their funders to make the results of their funded research permanently and freely available to the public. Such funders as the Wellcome Trust, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Max Planck Society not only insist that authors whose research they fund publish in OA journals but have established a new, broad-based, gold OA journal, eLIFE, which is completely free to authors “at least for an initial period”, according to the Web site. Finally, the growth of scientific research output itself, particularly in Asia and South America, is driving demand for more publication outlets. As the established literature (largely subscriptionbased journals) vies for position, largely on the basis of impact factors, editors are increasingly selective about what they publish in their journals. Many editors now deliberately keep their acceptance rate low to support a small denominator in the calculation of the average number of citations (the impact factor).

In this environment, it is not surprising that OA has grown into an important part of the scientific journal scene. Surprisingly, funding for authors appears to be available, either tacitly from their grants or as part of their institutions’ or funders’ commitment to making science as universally accessible as possible. The following are indicators that OA is not only here to stay but on the rise (in this context, we are talking about gold OA):

- The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), maintained by Lund University in Sweden, lists more than 8,000 OA journals and adds new titles daily.

- PLOS ONE published more than 14,000 articles last year alone.

- Major STM publishers, such as Elsevier and Wiley, are launching new OA journals. (Springer has been in this field for several years through BioMed Central and Springer OPEN.)

- Many societies are launching OA journals as companions to their flagships, part of the rationale being that, as rejection rates rise, disaffected authors submit their good, sound papers to competing journals, which results in added citations to the impact factors of competitors, after the original journal has invested time and resources in peer review.

The growth of OA has surprised many in the publishing industry. Although “freeing science”, to use the term coined by Spencer Reiss in his MIT Technology Review article,1 is a worthy ideal, some abiding concerns about how science should be set free need to be addressed by the editorial community, inasmuch as editors are the arbiters of soundness and quality in science.

There are a few concerns:

- Is quality control in science scalable? In other words, with the increase in output and the continued drive to publish, are resources available to provide critical peer review and, for accepted articles, stringent copyediting?

- Does bringing money into the supply side of journals (the authors) influence editorial and publishing decision making? It is a different dynamic when, for success, a journal must attain 500 subscribers (through marketing, “big deal” bundles, and so on) compared with the 100 articles that it must publish to be at break-even.

- Is there enough money in the academic system to support both subscription journals and faculty output?

- Is the proliferation of new journals— it seems that there is at least one OA journal for every “traditional” journal— providing a real service to the users of science, that is, the public and the professionals?

There is already evidence that some OA journals are not going to survive— they have no submissions and will die on the vine. There is also evidence that some OA journals, such as the PLOS journals, are strong. I suspect that in another decade or so, there will be a familiar landscape in scientific publishing: journals—whether OA or under access control—will thrive when they attract and publish the best papers, and the pecking order of journals will continue to drive author decisions on where to submit and editorial decisions on what to publish.

Reference

- Reiss, S. Science wants to be free: the argument for open access journals. MIT Technology Review. http://www.technologyreview.com/article/404007/science-wants-to-be-free/

MORNA CONWAY is president of Morna Conway, Inc., Shelbyville, Tennessee.