Abstract

Background: Scientific journals depend on mainstream media to disseminate research findings to the general public. We analyzed factors that contribute to media coverage of articles published in a large interdisciplinary journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

Methods: We assembled a database of 425 research articles published online in PNAS during 7 March–15 April 2011. Using the media-monitoring service Cision, we determined the number of news stories (“hits”) written about each article before 30 April 2011. We analyzed the database to explore our hypothesis that the amount of media coverage is influenced by inclusion of a summary of the article on the weekly PNAS tipsheet as either a 200-word press tip or an “Also of Interest” sentence, the order of the tips or AOIs on the tipsheets, the issuance of a non-PNAS institutional press release posted on the online news service EurekAlert!, and accompaniment by a cover image, cover tag, “In This Issue” summary, or commentary in the print issue.

Results: The 425 PNAS articles were cited in 2,483 media articles (2,063 online and 420 in print) during the study period. Articles highlighted in a PNAS summary or institutional press release received an average of 19.6 ± 1.5 and 14.2 ± 0.3 hits, respectively; articles with neither a tip nor a press release received 0.3 ± 0.2 hits. Articles highlighted on a tipsheet and in a press release received significantly more hits (47.9 ± 2.7) than either alone. The most hits were generated by articles whose tips were listed first or second on a tipsheet. Variables related to the print issue (such as cover images) had no effects on media coverage.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that coverage depends heavily on the coordination of media outreach activities by journals and institutional press offices.

Background

Dissemination of scientific research findings to the general public is an important task, but it is not the primary task of scientific journals, whose audience is usually limited to scientists themselves. To facilitate the sharing of scientific progress with lay audiences, many scientific journals have created media offices whose job it is to interact with journalists and communication officers in the hope that the journals’ content will be disseminated to the public.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) is one such journal. The media office consists of multiple science writers led by a media manager who edits their work. Each week, PNAS publishes 60–80 scientific articles in the biological, physical, and social sciences. On Wednesdays, the media office e-mails a tipsheet, which contains summaries of embargoed manuscripts, to registered science journalists who have agreed to honor the journal’s embargo policy. The summaries are also available to registered reporters through the online news service EurekAlert! (www.eurekalert.org) a week before the articles’ online publication in PNAS.

PNAS tipsheets include two types of summaries. The first, known as a tip, is about 200 words long; the second, an “Also of Interest”, or AOI, is a single sentence. Most tipsheets contain two to four tips and zero to five AOIs.

Each week, the PNAS science writers, media manager, and managing editor review a list of recently accepted manuscripts to identify the ones that should be highlighted on a tipsheet. Each participant reviews the list and identifies manuscripts that are likely to appeal to a lay audience. Although the tips and AOIs are selected case by case, a general rule of thumb is that manuscripts chosen for tips are generally deemed more newsworthy or require detailed explanations, whereas articles chosen for AOIs either will appeal to a smaller audience or can be summarized in a single sentence and need little technical explanation.

During that process, the participants also identify manuscripts to highlight in a section of the print journal known as “This Week in PNAS” (TWIP). These 200-word summaries are intended for a general scientific audience. They are published only after the articles appear in print, which is often several weeks after appearing online. Occasionally, a manuscript is designated to receive both a tip and a TWIP (this is referred to as a 2T) if it is considered of interest to the public and to the broad scientific community.

After the science writers make their selections, the media manager narrows the list, and the managing editor approves the final selections. The science writers then prepare the summaries, seek approval from the corresponding authors of the articles, and assemble a tipsheet. After distributing a tipsheet every week for several years, the media team sought to assess the variables underlying the extent of media attention that PNAS articles receive. Using a media-tracking service (Cision), we initiated a short-term project to determine the number of “media hits” (defined as unique news articles) that could be linked to each PNAS article published over the course of 6 weeks.

Methods

Two databases were initially created for use in this study. One contained a list of all PNAS articles that were published online from 7 March to 15 April 2011. We excluded from analysis all article types that did not reflect original research (biographical profiles, commentaries, invited reviews, corrections, letters to the editor, editorials, responses, perspectives, and retrospectives). For each PNAS article that we used, we collected the following information: article title, subject classification, online publication date, print issue date, presence or absence of a commentary, and presence or absence of a tip, AOI, or TWIP. In addition, we noted whether the article had been highlighted with a cover image or mentioned in a cover tag, the article’s classification as a specialty paper (such as a feature article, colloquium, or special feature), the presence or absence of an institutional press release (by the author’s institution or funding agency) on EurekAlert!, and whether a wire service (such as Associated Press, United Press International, or Xinhua) had publicized the story. We also defined seven levels of press interest for each article, according to the level of interest demonstrated by members of the media team during the selection process. In order of increasing interest, the levels were as follows: not marked for press interest, flagged by one or more science writers for potential press interest but was ultimately not selected, chosen for press interest but the summary was ultimately not included on a tipsheet, selected for an AOI, selected for a tip, selected for a TWIP, or selected for a 2T. Because TWIPs are targeted to a scientific audience and appear on the journal’s Web site only after a paper appears in the print journal, we assumed that the presence of a TWIP would not affect its mainstreammedia (MM) appeal. During our statistical analysis, we included the data on 2Ts with the data on tips and also analyzed 2Ts and TWIPs on their own.

A second database was created by using data provided by Cision. It contained a list of all MM articles that cited the specific text “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences” or “PNAS” and were published from 7 March to 30 April 2011. The end date was chosen to allow 2 weeks of media coverage of PNAS articles published on 15 April. We collected the following information on each MM article: title, outlet, language, publication date, publicity value, media type (print, Web, broadcast, or other), and circulation (for articles that appeared in print outlets) or number of unique visitors per month (for articles that appeared in online outlets). That information was provided to Cision by Compete. com. Publicity value is a number calculated by Cision to estimate the value of a given article in a particular media outlet. It is based on several factors, including the readership of the particular outlet and the length of the article.

We excluded from analysis all hits in the Cision database that had been written in a language other than English, duplicate hits, and hits that did not cite a PNAS article, usually because of the recycling of a URL. We also excluded PNAS, blogs, forums, microblogs, photo- and video-sharing sites, and social-networking sites.

After both databases were thoroughly reviewed and purged, the Cision database was synthesized into a spreadsheet in which each row corresponded to the coverage received by a single PNAS article: the total number of MM hits for the article, the sum of circulation values, the sum of publicity values, the sum of unique visitors per month, the date of first reference in MM, and the date of last reference in MM. Those data were merged with the PNAS database to link the MM data with the actions taken by the media office for each article.

Data displayed as means show error bars as ±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using Student’s t tests.

Results

From 7 March to 15 April 2011, PNAS published 425 research articles online. From 7 March to 30 April 2011, Cision reported 4509 English-language MM articles that referred to “PNAS” or the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.” Each MM article was skimmed to identify the PNAS article(s) to which it referred. Of the 4509 total Cision hits, 36 were excluded from further analysis because, when examined, the Web article no longer contained a PNAS reference. (The URL provided by Cision may have led originally to an article with a PNAS reference but URLs are sometimes re-used for new articles.) Another 12 MM articles were excluded because it was unclear to which PNAS article they referred. Cision hits that did not refer to a PNAS article that was published during the study period were also excluded from further analysis, leaving 2483 Cision hits.

Of the MM articles remaining, 420 were in the “Print” category (such as daily and community newspapers and magazines), 38 were in the “Other” media category (such as news services, industry research firms, freelancers, and associations), and the remainder were published online. Broadcast media (television and radio) were included in our analysis but resulted in zero hits.

Thirty-six PNAS articles were highlighted by the media office on six weekly tipsheets during the study period. Each tipsheet contained three to five tips and one to three AOIs for a total of four to eight article summaries per tipsheet.

We categorized each article according to the type of dissemination efforts that had been made on its behalf: 18 were highlighted solely on a PNAS tipsheet, 58 were highlighted solely by the authors’ institution, 10 were highlighted by the authors’ institution and on a PNAS tipsheet, four were mentioned on a PNAS tipsheet and were picked up by a wire service, and four received attention from PNAS, the authors’ institution, and a wire service. Most of the articles (338, 79.5%) were not mentioned on a PNAS tipsheet or in an institutional press release. As expected, those articles rarely garnered MM attention. The exceptions were 20 articles that garnered one or two MM hits, 10 that garnered three to eight MM hits, and two that received 20–30 MM hits. The remaining 306 articles (90.5% of the 338) received no MM hits.

We categorized each article according to the type of dissemination efforts that had been made on its behalf: 18 were highlighted solely on a PNAS tipsheet, 58 were highlighted solely by the authors’ institution, 10 were highlighted by the authors’ institution and on a PNAS tipsheet, four were mentioned on a PNAS tipsheet and were picked up by a wire service, and four received attention from PNAS, the authors’ institution, and a wire service. Most of the articles (338, 79.5%) were not mentioned on a PNAS tipsheet or in an institutional press release. As expected, those articles rarely garnered MM attention. The exceptions were 20 articles that garnered one or two MM hits, 10 that garnered three to eight MM hits, and two that received 20–30 MM hits. The remaining 306 articles (90.5% of the 338) received no MM hits.

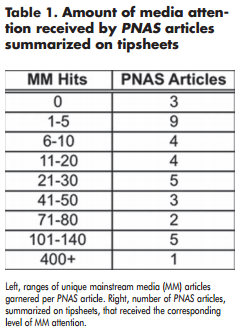

Of the articles that were promoted on a PNAS tipsheet, three received no media coverage, nine received one to five MM hits, eight received six to 20 MM hits, 10 received 21–80 MM hits, and six received more than 100 MM hits (Table 1).

An outlier

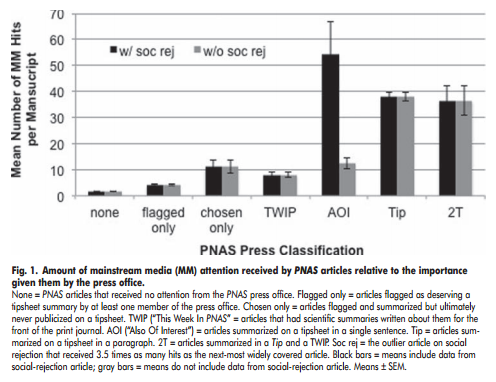

The most highly covered article received 472 MM hits, 3.5 times as much as the next-most widely covered article, which received 136 MM hits. The most highly cited article explored social rejection (“soc rej”) and revealed that the brain processes emotional pain and physical pain in a similar manner.

Normally, an article with such broad appeal might receive a tip; however, this article received an AOI because the subject matter was easily summarized in a single sentence. For that reason, it is not fair to assume that the level of media attention garnered by the article is representative of all articles that received AOIs rather than tips.

The author’s research institution also sent out a press release about the social-rejection article, and the press release was posted on EurekAlert! in addition to the PNAS summary. Furthermore, two wire services picked up and disseminated the story. Clearly, multiple factors contributed to the widespread media coverage of the article.

Because of the striking amount of media attention garnered by the social-rejection AOI and because the attention was not representative of most other articles (Figure 1), we considered this AOI an outlier that could skew overall trends. We therefore used two approaches in representing the data: using median values and using mean values with and without the inclusion of the social-rejection article.

Amount of media coverage relative to PNAS press classification

To explore the efforts of the PNAS media office with regard to MM attention garnered by each article, we plotted the average number of MM hits for each article on the basis of its press classification (Figure 1). As expected, the 319 articles that received no attention from the PNAS media office received little MM attention (mean, 1.7 MM hits/article). The 39 articles that were flagged as interesting by at least one member of the media team but not chosen for a tip or AOI (“flagged only”) received more than twice as many hits as articles that received no attention from the media office. The 13 articles that were chosen and summarized but not included on a tipsheet (“chosen only”) received nearly three times as many hits as articles that had been flagged for press interest but not ultimately summarized. We found that articles that were summarized but not included on a tipsheet received about the same amount of media coverage (P = 0.9) as articles that received an AOI (when the social-rejection article was not included). Therefore, it might be suggested that AOIs do not elicit substantial media coverage. However, we propose that the result reflects the small sample size and the fact that authors’ institutions disseminated press releases for three of the 13 “chosen-only” articles and thereby elicited substantial MM coverage of those articles. When the median numbers of hits for the various classifications were compared, only articles with an AOI or a tip had median values higher than zero; this means that most articles that were not promoted on a tipsheet received no MM attention (i.e., most of their values were zero).

To explore the efforts of the PNAS media office with regard to MM attention garnered by each article, we plotted the average number of MM hits for each article on the basis of its press classification (Figure 1). As expected, the 319 articles that received no attention from the PNAS media office received little MM attention (mean, 1.7 MM hits/article). The 39 articles that were flagged as interesting by at least one member of the media team but not chosen for a tip or AOI (“flagged only”) received more than twice as many hits as articles that received no attention from the media office. The 13 articles that were chosen and summarized but not included on a tipsheet (“chosen only”) received nearly three times as many hits as articles that had been flagged for press interest but not ultimately summarized. We found that articles that were summarized but not included on a tipsheet received about the same amount of media coverage (P = 0.9) as articles that received an AOI (when the social-rejection article was not included). Therefore, it might be suggested that AOIs do not elicit substantial media coverage. However, we propose that the result reflects the small sample size and the fact that authors’ institutions disseminated press releases for three of the 13 “chosen-only” articles and thereby elicited substantial MM coverage of those articles. When the median numbers of hits for the various classifications were compared, only articles with an AOI or a tip had median values higher than zero; this means that most articles that were not promoted on a tipsheet received no MM attention (i.e., most of their values were zero).

Articles that received a tip (19) or 2T (6) garnered the most MM attention of all articles studied (excluding the social-rejection article). Because articles in both categories received equivalent amounts of attention from the PNAS media team (P = 0.9), we conclude that TWIPs did not make a substantial contribution to the amount of MM coverage received by an article. This lack of influence is most likely due to the delay of the TWIPs relative to the online publication of the articles that they summarize and may also be partly due to the growing use of the Internet— instead of print media—as a news source. Similarly, we found no increase in MM coverage of articles that were highlighted in other ways in the printed journal, either by the presence of a commentary, a cover image, or a cover tag or by being classified as a specialty paper (data not shown).

The effect of tipsheet order on media coverage

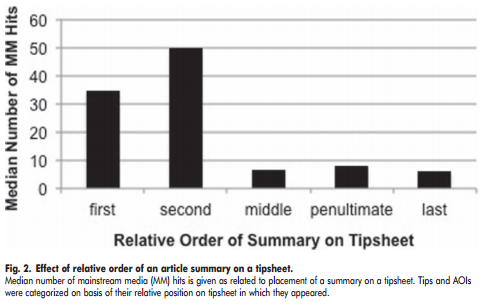

Assuming that not every tipsheet is read to completion by all journalists, we tested the hypothesis that articles mentioned at the top of each tipsheet would garner more MM coverage than those in the middle or at the bottom of a tipsheet. The data (social-rejection paper data excluded) show that to be true: Tips in the first and second position on a tipsheet consistently received several times more MM hits than summaries (tips or AOIs) in the middle or at the end of a tipsheet (Figure 2). (The social-rejection paper was summarized as the first of three AOIs preceded by five tips on its tipsheet and was therefore included in the “middle” group. Figure 2 shows medians to represent the trend more accurately.)

Assuming that not every tipsheet is read to completion by all journalists, we tested the hypothesis that articles mentioned at the top of each tipsheet would garner more MM coverage than those in the middle or at the bottom of a tipsheet. The data (social-rejection paper data excluded) show that to be true: Tips in the first and second position on a tipsheet consistently received several times more MM hits than summaries (tips or AOIs) in the middle or at the end of a tipsheet (Figure 2). (The social-rejection paper was summarized as the first of three AOIs preceded by five tips on its tipsheet and was therefore included in the “middle” group. Figure 2 shows medians to represent the trend more accurately.)

That result is complicated, however, by the fact that tips are always listed before AOIs on PNAS tipsheets. Furthermore, tips are often reserved for stories deemed most complex or of highest public interest by the PNAS media team. Although there are no data to support that conjecture, it might also be true that the person compiling the tipsheet arranges the content so that the tip that is the most interesting, in the person’s opinion, appears at the top.

Effect of all dissemination efforts on amount of media coverage

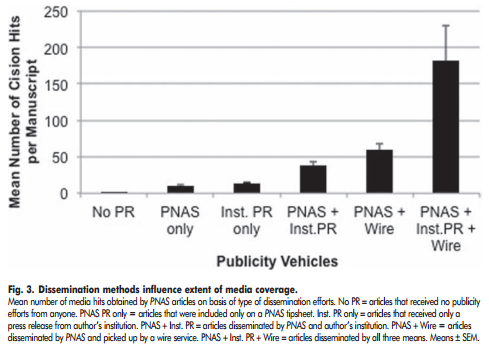

During the study period, the 18 articles highlighted only in a PNAS summary and the 58 highlighted only in a press release from the authors’ institutions received comparable averages of 10.7 ± 0.4 and 14.2 ± 0.4 MM hits per article, respectively (P = 0.5); the 338 articles that had neither a tip nor a press release received 0.1 ± 0.02 hit per article. The 10 articles highlighted both on a tipsheet and in an institutional press release received about three times as many hits (39.0 ± 0.5) as those publicized by either alone. Coverage by a wire service increased the number of MM hits for four articles included on a PNAS tipsheet to 59.8 ± 0.8. It is notable that no article was posted on EurekAlert! by an author’s institution and picked up by a wire service without having been summarized by PNAS. The four articles that received attention from all three parties received an average of 181.8 ± 1.2 MM hits in the study period (Figure 3).

During the study period, the 18 articles highlighted only in a PNAS summary and the 58 highlighted only in a press release from the authors’ institutions received comparable averages of 10.7 ± 0.4 and 14.2 ± 0.4 MM hits per article, respectively (P = 0.5); the 338 articles that had neither a tip nor a press release received 0.1 ± 0.02 hit per article. The 10 articles highlighted both on a tipsheet and in an institutional press release received about three times as many hits (39.0 ± 0.5) as those publicized by either alone. Coverage by a wire service increased the number of MM hits for four articles included on a PNAS tipsheet to 59.8 ± 0.8. It is notable that no article was posted on EurekAlert! by an author’s institution and picked up by a wire service without having been summarized by PNAS. The four articles that received attention from all three parties received an average of 181.8 ± 1.2 MM hits in the study period (Figure 3).

Conclusions

Many factors affect the amount of media coverage that a journal article receives. Several of the factors are outside the control of the pertinent media offices (such as the trending news stories of the week and the subject matter itself). We do not assume that press-office efforts are the only factor that determines the amount of MM coverage, and our small, short-term study can only approximate the effect of PNAS efforts on the press coverage garnered by its articles. A longer-term project could reveal more important trends but is not feasible because of the need to hand correlate Cision entries with published PNAS articles. Those limitations notwithstanding, the relationships revealed in our study are those one might expect to observe as a result of the efforts of a media office that is skillfully choosing the best articles to highlight.

Without a doubt, PNAS summaries are effective tools for reaching the general public through the MM. Tips, especially those listed first or second on a tipsheet, generally garner substantial press coverage and more than AOIs do. It is also clear that a press release from an author’s institution is valuable in that it more than doubles the amount of coverage received. The factor that predicts an article’s success in the MM most strongly by far is whether it gets picked up by a wire service. We conclude that collaboration between media offices and journalists is effective in disseminating scientific research to the general public and should be encouraged.

CATHERINE M KOLF is senior communications specialist, media relations office, department of marketing and communications, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, and ANN GRISWOLD is principal, SciScripter Writing & Editing, LLC, Baltimore, Maryland.