What does it mean to be an international journal? In an online publishing and submission landscape, almost all journals, even those with a specific location in their title, are effectively international in the sense that they may have readers around the world and accept submissions for any researcher, anywhere.

But is that enough to be truly international? In this issue of Science Editor, three articles explore what it means to be an international, geographically diverse journal or organization and provide suggestions for improvement.

Global Balance

As discussed in a recent Science Editor Newsletter,1 The makeup of an editorial board is an area where journals may try to improve their international reach, adding members from across the globe. But as Rafael Araújo and Geoffrey Shideler report in the article based on their award-winning abstract from the CSE 2019 Annual Meeting, Cultural and Geographical Representation in the Editorial Boards of Aquatic Science Journals, the extent of many editorial board’s geographic diversity does not always compare to the geographic diversity of their authors.

Specifically looking at aquatic science journals, Araújo and Shideler find that some countries, particularly the US, have an overrepresentation on editorial boards whereas others, particularly China, are underrepresented compared to how often authors from those countries publish in the journal.

The authors refer to this difference as either an editorial surplus or deficit and provide a framework for determining where a journal stands: take the geographic representation of the editors (e.g., 50% US-based editors, 20% Canada, 10% Japan) and compare it to the country of origin for published articles in that journal. For example, a journal may have 60% of its editors based at a US institution, but only 40% of the articles published in a year originate in the US. I highly suspect that the findings they show in Figure 1 for aquatic journals (that is, a surplus for US, Canada, and most of Europe, and a deficit for most of the rest of the world) is fairly common.

Importantly, Araújo and Shideler also find a relationship between the geographic diversity of journal editors and Scimago journal rank, as journals with more diverse editorial boards tended to be ranked higher. While causation can’t be determined (for example, higher ranked journals may have an easier time recruiting international editors), they did find that geographically diverse journals were rarely low-ranked. This implies a likely virtuous cycle, wherein international editors help attract the best research from around the world, helping to attract more top international editors, and onwards and upwards.

Geographical Diversity

Of course, it is important to remember that the term “international” can encompass every other country than a journal’s home country, so it’s important to avoid thinking of it as a local/international binary. In her article, Siân Harris, a communications specialist at INASP, outlines ways we can move Toward Global Equity in Scholarly Communication, challenging editors to think about diversity and inclusion at their journals and ensure that “geographical diversity” is not forgotten. As an example, when weighing the international makeup of authors or reviewers, it is not uncommon to see, for example, the UK—a country, given the same weight as Africa—a continent. As she states, “a researcher from Ethiopia is no more represented by a journal paper from South Africa than a researcher from Croatia is represented by a paper from the UK.”

“A researcher from Ethiopia is no more represented by a journal paper from South Africa than a researcher from Croatia is represented by a paper from the UK.”

One of the reasons this is important to consider is that researchers in low- and middle-income countries continue to face significant challenges and barriers to acceptance in a scholarly communication system dominated by the “Global North.” Many journals when selecting articles for publication require that the research be “novel and significant,” but to whom? Institutions in low- and middle-income countries with significantly fewer resources than their wealthier counterparts may not be able to carry out the first-ever trial of a new drug or procedure but attempts to replicate trials in novel environments and populations should be seen as significant and valuable contributions to global research. There are signs that this is starting to be recognized (see for example, this recent editorial2 in an American Heart Association journal), but more needs to be done. Luckily, Harris provides additional specific recommendations for improving global diversity in journals.

International Collaborations and Partnerships

Another way that journals can participate internationally is by partnering with local journals through partnerships, such as the African Journal Partnership Program (AJPP), to which the Council of Science Editors provides support. In their article, Fanuel Meckson Bickton, Lucinda Manda-Taylor, Raymond Hamoonga, and Aruyaru Stanley Mwenda describe the Challenges Facing Sub-Saharan African Health Science Journals and Benefits of International Collaborations and Partnerships.

Considering the population size of sub-Saharan Africa and the disproportionate disease burden affecting this population, all things being equal, research output from these countries should be high; however, as the authors outline, sub-Saharan Africa accounts for “less than 1% of the world’s research output.” They suggest this is in large part due to a lack of support at an institutional level, financially, but also for research, writing, and editing mentorships and training that would help improve the quality of published research from these countries.

This training is crucial because researchers in sub-Saharan Africa still want to, and are sometimes expected to, publish in overseas journals with high Impact Factors. However, even when the quality of the research and writing is high, “high impact” journals sometimes view the research coming out of Africa as not “novel” and meant for African audiences only.

One of the goals then of programs like AJPP is to build up the infrastructure of African journals so they can support local research through training and mentorship, but also by giving them a high-quality avenue for publication. Running a journal as an editor-in-chief can be tough, even when there is institutional and editorial office support, both of which can be lacking for African journals. Thus, AJPP partners African journal editors with more established US and UK journals to provide mentorship and training in the hopes of improving the quality and visibility of the journals so they can attract higher quality manuscripts and raise the profile of African research overall. The authors conclude by offering their hopes for the future and ways journals and editors can help contribute.

To be considered international a journal can’t just recruit a few editors from prestigious non-US institutions and be done with it.

A key takeaway from these articles is that to be considered international a journal can’t just recruit a few editors from prestigious non-US institutions and be done with it. Including an international perspective at a journal is an ongoing process and more can be done to improve editorial deficits, support true geographic diversity, and develop global partnerships.

Also in this issue of Science Editor, Lee Ann Kleffman, Managing Editor of Neurology Genetics, presents her research into how authors determine where to submit their research. Using author surveys, she found that “journal reputation” was by far the number one determinate for where authors preferred to publish. Interestingly, the survey provided “Impact Factor” as a separate option and it tied with “journal audience” as a secondary factor. How authors are exactly defining “reputation” is hard to know for sure, but taken at face value, the research suggest there are elements beyond Impact Factor that journals and editors can work to improve to boost their reputation, and thus increase submissions.

This issue also marks the last batch of Meeting Reports from the 2019 CSE Annual Meeting in Columbus, Ohio. Some of the more inventively named sessions covered include “I am Sorry, Who Are You Now? Navigating Mergers and Acquisitions in the Vendor Space”; “Building and Managing a Taxonomy: How to Manage All of the Cooks in the Kitchen”; and “A Picture’s Worth 1,000 Words: Disseminating Research Through Graphical and Visual Abstracts”. There are also helpful articles on changes to the AMA Style Guide, an update on the Manuscript Exchange Common Approach (MECA) Initiative, tips for Turning Your Research into an Article/Poster, and much more.

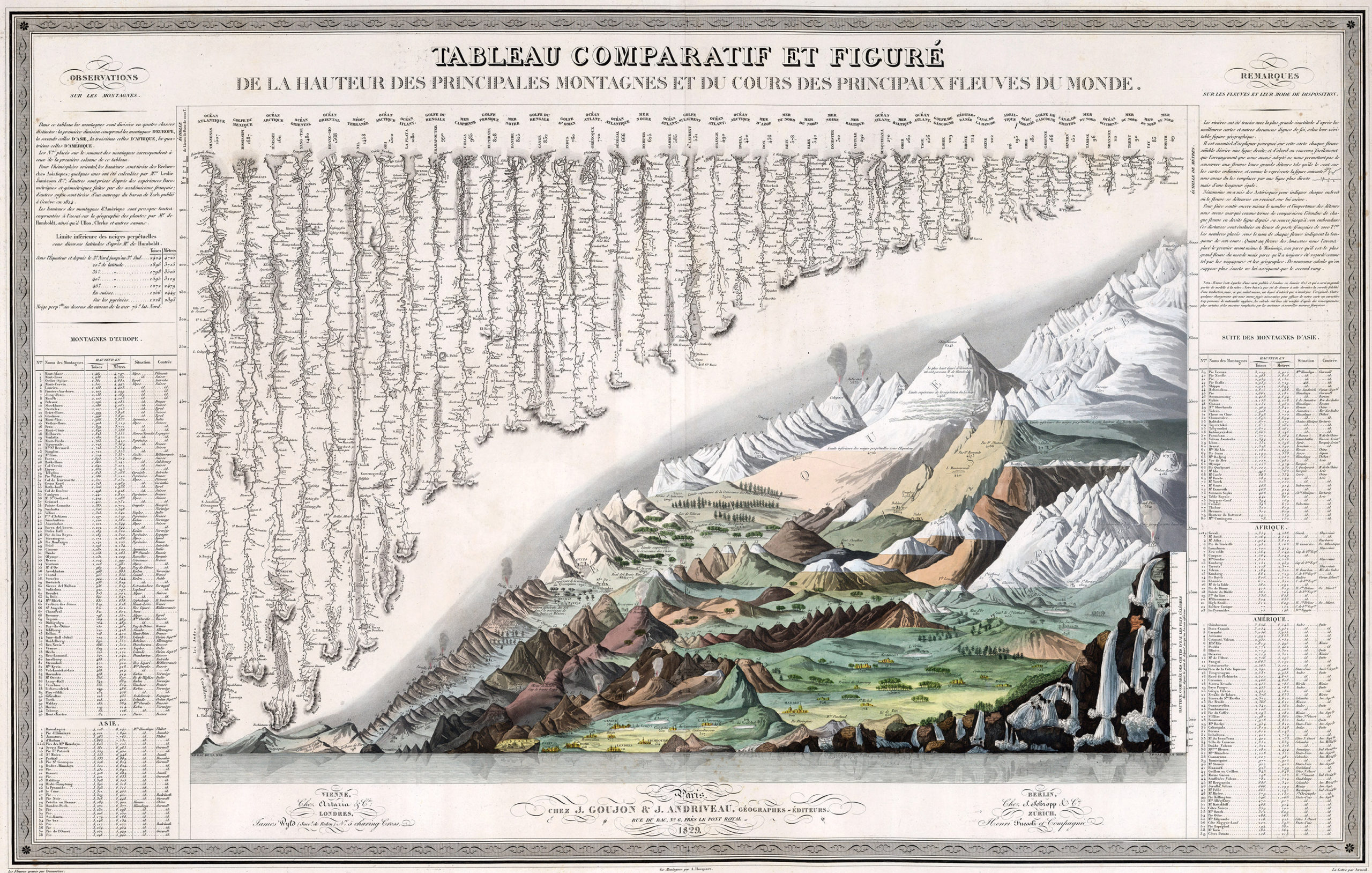

I will conclude this introduction to this special issue of Science Editor on International Perspectives by highlighting the cover image, a detail from “Des Principales Montagnes et du Cours des Principaux Fleuves due Monde” published by J. Andriveau-Goujon in 1829 (courtesy of the David Rumsey Map Collection, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/dl6cs63). The full version of this map is below, and it represents an early data visualization, comparing the sizes and features of the major mountains and rivers known at that time. The image provides an international assessment of the world’s highest peaks and longest rivers merging them all together into one beautiful graphic. A metaphor perhaps, but also a lovely work of art either way.

References and Links

- https://www.csescienceeditor.org/newsletter/august-2019-international-perspectives/

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006280

- https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~279649~90052835:Des-Principales-Montagnes-et-du-Cou;JSESSIONID=8942acd3-268e-4113-a3b5-0b665b1e02fe;JSESSIONID=b778f975-5322-4624-b8fe-6ab977be18b0?qvq=q%3Ahumboldt%3Bsort%3Asortid%2Cpub_list_no%2Cseries_no%2Cseries_no%3Blc%3ARUMSEY%7E8%7E1&sort=sortid%2Cpub_list_no%2Cseries_no%2Cseries_no&mi=79&trs=351

Sections of this Viewpoint are adapted from the August and December 2019 editions of the Science Editor Newsletter.