MODERATOR:

Shari Leventhal

Managing Editor

American Society of Nephrology

Washington, DC

SPEAKERS:

L Lee Hamm

Senior Vice President and Dean of the School of Medicine and the James R. Doty Distinguished Professor and Chair

Tulane University School of Medicine

New Orleans, Louisiana

Kenneth Heideman

Director of Publications

American Meteorological Society

Boston, Massachusetts

Sheehan Misko

Director, Publications

American Association for Clinical Chemistry

Washington, DC

Meagan Phelan

Science Press Package Executive Director

American Association for the Advancement of Science

Washington, DC

REPORTER:

Kristen Hauck

Assistant Managing Editor

American Association for Clinical Chemistry

Washington, DC

We have all dealt with crises big and small over the course of our professional lives. The panelists for this session, moderated by Shari Leventhal, offered personal stories and shared some of the lessons they have learned from dealing with a variety of situations ranging from natural disasters to the dreaded retraction.

L. Lee Hamm began by recounting the experience of being trapped with colleagues at Tulane University during Hurricane Katrina. Hamm and others spent 6 days waiting for help to arrive, and he shared 3 main takeaways from that experience. First, he said, know what is important. In this case, that was water, food, power, and security—all those things we take for granted were suddenly scarce. What if the elevators are out and you need to move patients between floors? Put your young, strong residents to work, it turns out. Second, communication is vitally important. What happens when your primary forms of communication—cell phone, email—are no longer available? What happens when even your backups fail? Post-Katrina, Tulane implemented a communications system in which everyone can be reached at a non-Tulane email address and all information is backed up off site. Third, plan ahead. Hamm cautioned, however, that the worst problems are often those you do not anticipate.

Ken Heideman next shared a tale of resilience and teamwork following a “publishing disaster.” In July of 2010, an IT error led to the loss of 6 months of data, including submitted manuscripts and author data. After resisting the initial urge to point fingers, the editorial team jumped into triage mode, identifying which papers had been affected and where materials could be retrieved from outside vendors. Unfortunately, some papers were entirely lost, and the team needed to ask authors to resubmit everything.

According to Heideman, complete transparency was key to inspiring others to rally around the cause and find creative solutions. Having the support of the organization’s leadership made it easier to tackle the problem.

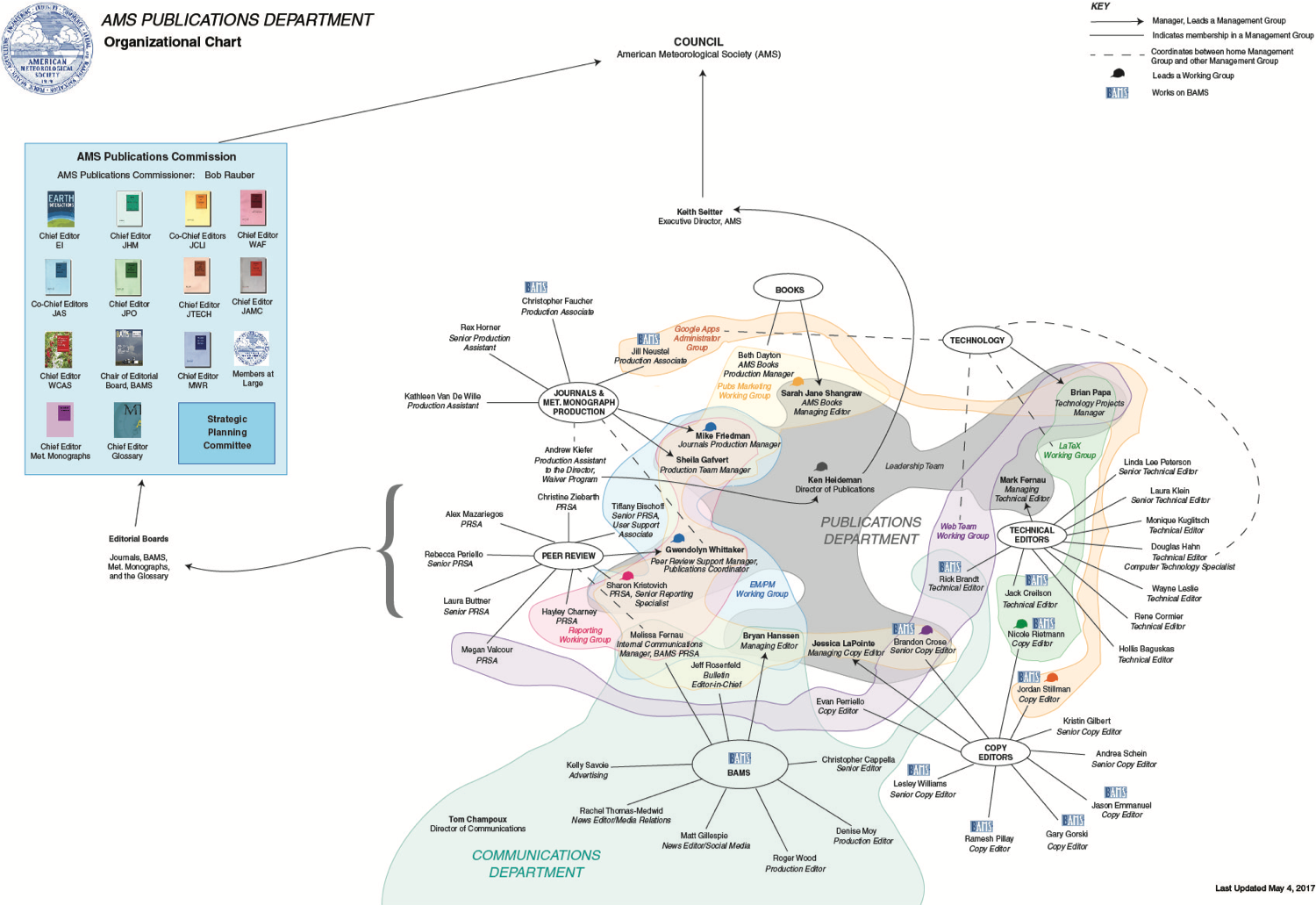

Heideman cited several positive outcomes: First, this was the push the department needed to begin outsourcing more tasks, which was a great success and prompted other departments to follow suit. Also, the team experienced a new level of bonding in the face of this crisis that is still felt 8 years later. Gallows humor, says Heideman, is a great way to break the tension. Finally, a better, stronger organizational structure resulted. Groups and subgroups with different managers have proven better able to prevent or address problems.

Personnel changes are a less extreme sort of crisis but can still rock a team to its core. Sheehan Misko shared her experiences managing an editorial team through a series of staffing changes that ultimately led to surprising new opportunities.

After the launch of a new journal, The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine, finding someone to serve as a champion for that publication proved to be a challenge. An individual was hired but was not a good fit and was ultimately let go. It became necessary for Misko, the Director of Publications, to step in and handle tasks such as peer review and manuscript check-in. As an interim measure, the department began outsourcing certain tasks to J&J Editorial. However, what the journal really needed was an experienced and qualified person to take ownership, and that person was proving to be difficult to find.

The solution came in the form of a long-time employee who was looking for a change. This individual expressed interest in the position but was also considering relocating across the country and wanted to explore telework options. Misko proposed to the leadership that the employee be allowed to telework full time, a first for the organization, which also served as an incentive for that person to take on an expanded and potentially daunting role. That employee’s existing work was shifted to J&J, and the end result was a win for everyone.

Like Heideman, Misko also credited transparency, saying that sharing news with one’s team immediately gets everyone invested in sharing the load right from the start. Her advice to others dealing with a similar situation: Look to your team because they are more valuable than you might give them credit for. If your organization’s leadership is forward thinking, there may be room to try out-of-the-box solutions.

The final speaker, Meagan Phelan, detailed the aftermath of high-profile retractions of Science articles that had the potential to negatively impact public perception of journals and, more broadly, the scientific enterprise. Such scenarios raise 2 strategic questions for journals to answer: How to respond calmly when issues are nuanced and/or still being resolved in order to avoid being cornered into too rigid a stance, and how to use such cases as opportunities to highlight the many strengths of the scientific review process?

Science has been developing a set of best practices for responding to such high-profile cases. Phelan considers it vital to respond in a timely manner, keeping in mind that reporters who will be filtering the story to the public are up against tight deadlines. Also, it is important to answer all questions directly, even if that means conveying uncertainty. Finally, use the moment. A high-profile controversy can be an opportunity to raise awareness of what works well about scientific publishing. Science has identified the following points to stress whenever possible: 1) Retractions are relatively rare overall; 2) journals are typically quick to alert the community (including reporters) to problems via multiple avenues; 3) enabling scientists to replicate, confirm, or refute findings is integral to the scholarly publishing process; 4) peer review is rigorous and constantly improving but is by nature imperfect; and 5) although misconduct does occur, most scientists can be trusted to act with integrity.

To ensure accuracy of information and a unified front, Phelan emphasized the importance of involving others who have been a part of the life cycle of the paper, such as the Editor-in-Chief and Executive Editor, in crafting a response. One should anticipate controversies before they become unmanageable and should have several possible responses drafted, reviewed, and ready to go.

Although the details of each situation varied, the speakers agreed that transparency, a team-oriented approach, and strong communication are essential tools for mitigating any crisis.

Link to Presentations