Kathy Stern, the Graphic Arts Director at the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), is familiar with the adage “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Over her 29-year career with the NEJM, Kathy has drawn and overseen countless images telling myriad stories and has thus contributed millions of “words” to the information shared with NEJM readers. Images range from in-house illustrations drawn by medical illustrators, to line art graphs, photographs submitted by physician-authors, still images captured from videos created in-house, interactive online elements, and more. In this interview, Kathy discusses how she started in the production department back in the days of paste-up layout and now oversees a department of more than 20 employees working with state-of-the-art digital tools.

Science Editor: How did you get started with your career at the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM)?

Kathy Stern: I started out working in a production facility that wasn’t even part of the editorial office. We communicated with a production coordinator in Boston (where the NEJM editorial offices are located) who worked directly with the editors. NEJM was one of several products that the production facility of the Massachusetts Medical Society served, but it was, by far, the biggest product.

It was a massive amount of detail work. Everything was done with manual layout with precision cutting knives, acetate, and wax. We would create 14 different proofs that went out to 14 different people. Our main focus was the level of detail; everything had to be exactly right. If you found an italic period, you fixed it; you’d redo the entire page because of an italic period.

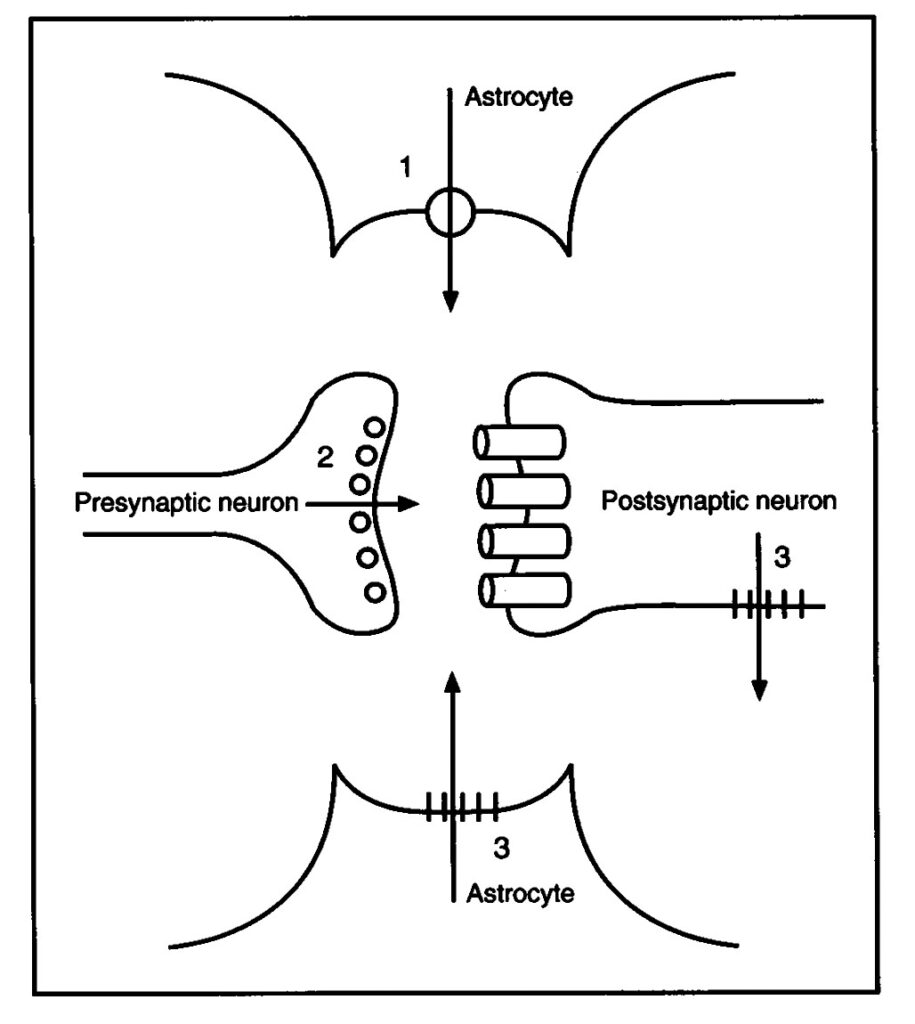

We moved things half a point if the editorial office said to. Every preposition, every punctuation mark, every half point had to be the way the editors said. Back then, we didn’t query the editors directly. We queried a coordinator, who filtered the queries to the manuscript editors, who then filtered the queries to the deputy editors. We spent a lot of time doing multiple quality assurance passes. In addition, we didn’t have in-house graphics; we published illustrations that had been supplied by authors (Figure 1)1 rather than drawing them ourselves.

SE: Now, you’re in charge of all the graphic arts at NEJM. You’ve come from doing the tiny little details and the italic periods to working on a much larger scale. What has this shift been like?

Stern: Essentially, we still do worry about the italic periods and the tiny details. I first moved to the editorial office kind of as a fluke. Before I came to NEJM, I had worked as an illustrator and graphic designer for 12 years in architecture and ad agencies and decided that really wasn’t the field that I wanted to be in (especially ad agencies!).

In fact, I had decided to go to medical school and was taking night classes in the Harvard Extension School pre-med program. I noticed a job advertisement for being a proofreader at NEJM, which I thought would be a great way to make money to support my attempt to go to medical school.

I was working at NEJM because I was interested in medicine—not because I was interested in italic periods—but one day, someone needed a birthday card for one of the editors, and they asked the people at “comp,” as they used to call us (for “compositors”), to make the card. I was an illustrator, so I drew it, and the people in the editorial office really liked it. It was a picture of a pink Cadillac driving away into the distance, kind of retro.

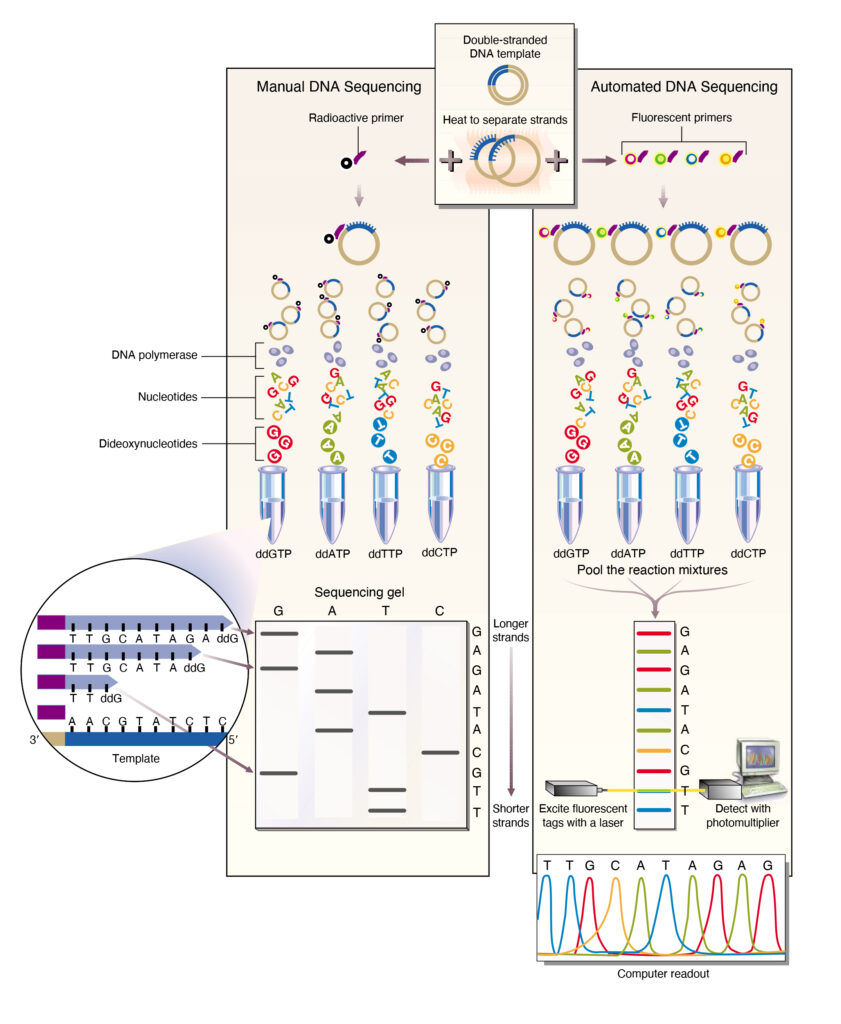

The next thing I knew, the editor-in-chief called me, saying, “I have a job for you.” He wanted me to illustrate a B-cell for an article about HIV, which was a huge issue in the early 1990s. I did the illustration with a very rudimentary version of Adobe Illustrator. It was a circle with a gradient and a square; the receptors were basically all squares and circles. Even doing gradient shading was a big deal. With this tool, I couldn’t see what I was drawing; I had to move things around, click a button, and wait to see it render. It was a laborious process to create a simple drawing. But the editors liked it, and they asked me to do another one. Finally, I drew quite an elaborate version of a DNA molecule (Figure 2).2

Those drawings look rudimentary now—you could probably get a computer to make one if you pressed a button. Back then, it took days and days and days to draw this molecule. Fortunately, the editor-in-chief loved that molecule, and I was asked to join the editorial office. My medical background at that time consisted of those pre-med courses—nothing like the usual medical illustrator training.

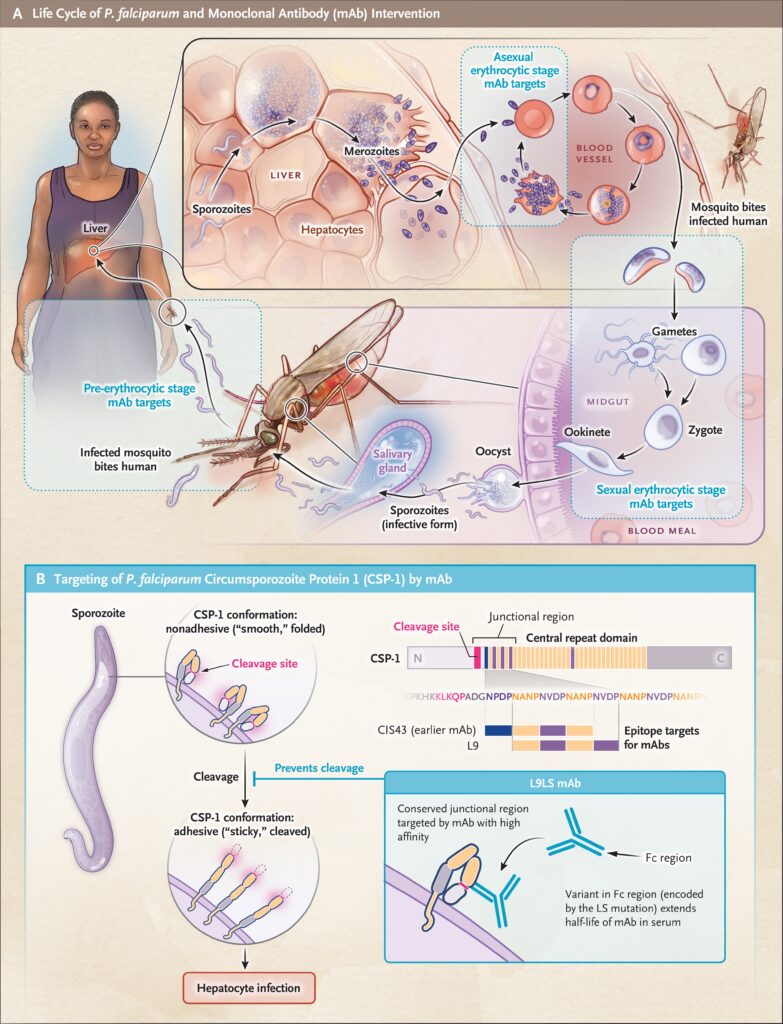

There were no other graphic artists or illustrators in the editorial office. I had a tiny office, like a broom closet, with a desk and a computer. I spent a lot of time in the Harvard Medical School Countway Library (the building that houses NEJM), down in the stacks looking at anatomical references and other journals. It was important to be in the library and working directly with the editors. Every time there was a medical illustration, which was rare, the editors conferred with me. They would set up a special meeting and describe what the illustration was about, and I’d give them paper drafts. It was such a different process from today. With the digital tools that are available now, we can create quite sophisticated illustrations (Figure 3).3

SE: How many people do you currently oversee in your department?

Stern: We have 15 full-time employees, plus about 6 part-time employees, mostly working on videos. The changes have been dramatic. Not only did we become totally involved in the editorial process, but as the need for illustrations grew, we were the only production team involved in the developmental aspect of creating content. In the past, we always did it before the article was accepted. Once the article was accepted, my job became like a production job.

The website started being developed around the same time that we started having regular medical illustrations, so the illustrators became involved in the technical part of making images for print, which was a different process from preparing images for the Web. The department grew on both ends. I hired medical illustrators as soon as I could, as well as people on the technical side for production.

I understood print production really well but not Web production. Once we started learning how to handle Web production, it exploded from there, because once we got online, we started getting involved in multimedia. Multimedia meant the involvement of even more people in both development and production.

If we were still just doing print medical illustrations, we would absolutely still employ several accomplished medical illustrators who understand medicine. I hired these people because I was a graphic designer, an illustrator, but not a person with a strong medical background. When I started doing medical illustrations, I realized that it was a lot more fun and a lot easier than going to medical school <laugh>. I continued taking night classes in topics like molecular biology, but I wasn’t worried about getting into medical school.

SE: What types of graphics and multimedia are you managing, handling, and developing?

Stern: The graphic arts department handles two kinds of graphics: in-house illustrations are developed in conjunction with authors and the deputy editors, and the other graphics type involves redoing submitted material, typically black and white line art. Line art is also in color now, so “line art” is a kind of a misnomer, but that’s what we call it. There was a completely different technical process for line art than for color illustrations.

When we had paper layout that went to the printer, the printer would send back elaborate proofs, and we would have what seemed like 5000 review stages. But when we got to desktop publishing, the whole process changed. It became easier to integrate color illustration. In the old days, we had to know exactly which pages included color images. We weighed all the information in advance and pasted up the pages in an elaborate way. The printer made four-color plates, and it was expensive and time-consuming. These days, you can make a four-color plate by pressing a button, so we put color on practically everything.

NEJM gets new editors-in-chief fairly seldom. When we do, in my experience, having been here nearly 30 years, each new editor has ideas for updating the journal. When I started, the editor wanted to spearhead a print redesign, but it was also the beginning of the website. As the Graphic Arts Director, I would sit in on meetings, and designers would come in and say, “Let’s have more color pages, let’s have more drawings, let’s create something that’s more visually appealing than the old, very simple way of medical and academic journals.” Well, academic journals aren’t really Vogue magazine! We were working within the constraints of inexpensive web presses, but the designers wanted to create something more appealing. That’s one reason we started using more color. The other reason is that we started recreating author-submitted graphics to match our specifications.

We never touch the data, but we change typefaces and make the font a size that looks good in print, so the graphics become more consistent. Starting in the 1990s, authors began sending in videos and screenshots of the medical imaging they saw on their computer.

There was more discussion of how we could show other kinds of medical imagery. We had to start creating graphics that could be viewed online. The Web is much more visual than print. We needed lots of previews, little thumbnails for every element. This process changed how graphic NEJM was.

As the Web grew in popularity and medical technology became more digitized, it became important to represent technologies such as ultrasonography online. We started doing rudimentary video editing to show author-submitted medical images online.

For Videos in Clinical Medicine,4 we work with groups of authors who create videos specifically for us. So, we had to learn video technology and captioning technology.

Several years ago, the editor-in-chief introduced the idea of publishing video summaries of research articles. These “Quick Take” videos5 became quite popular and involved a lot of video-creation technology.

Some multimedia elements are hard to use on cellphones. But it’s pretty much a story of technology in medicine, in publishing, and in social media—and in life. So much is conditioned by what people are using and by what clinicians are using. Since our audience is primarily clinicians, we stick to what they use. At this point, everyone uses cell phones and handheld devices.

SE: What type of software are you using? Is there more beyond Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator?

Stern: We use Adobe After Effects and Premier Pro for video editing and post-production tools, plus audio-editing tools, Zoom, and Riverside. There are various products for recording interviews, meetings, panel discussions, and podcasts.6

SE: Several years ago, we began using XML-based software for manuscript editing at NEJM. One useful aspect is that XML and Typefi enable the incorporation of artwork into proofs. Such changes must have affected how you turn what manuscript editors give you into the forms needed for layout and online posting.

Stern: Typefi intermediates between XML and Adobe InDesign. It’s more automated and in some ways a lot easier. But it can make things less flexible, too. The same thing is true with online display. Whatever Web provider we have and the technical limitations that are imposed on us are always reflected in what kinds of graphic displays we can make. This issue is still evolving, and changes are often made from a business perspective. In some ways, it makes things easier, and it also makes things more limited for graphic artists—but it does make things faster. There’s less time doing work by hand.

SE: It feels like things are moving very fast.

Stern: When you’re an illustrator, you want to do hand work. But there’s a lot of paraphernalia around getting articles processed and published and displayed regardless of the medium—whether it’s print or online or whatever is coming in the future. It’s nice to have those parts automated.

SE: What sort of skills or abilities are essential for your job? You said that back in the day it was really a good eye for detail. What is relevant today?

Stern: It’s still an eye for detail, especially at NEJM. The vast bulk of the work in our department goes to medical illustration. For medical illustrators, the most important skills are a good scientific background, an ability to draw, and an ability to render images in various media. A lot of our illustrators use 3D modeling, which is really complicated, but they don’t use it for the final product. They use it to create an armature for rooms or spaces or people in motion. They start off with a 3D model to get a basic perspective or look or motion, but they draw over it; just using raw 3D modeling can result in a not very pleasing effect. The main skills are understanding the science, understanding how to communicate, understanding hierarchy and organization, and being able to draw and use the technical tools necessary to create the kind of image or multimedia display we want.

One of our newer skills involves publishing videos geared toward a YouTube audience, which need a sense of narrative. Not only is there a sense of spatial organization and hierarchy and communication that most graphic artists and illustrators need in order to work at a medical journal, but now we need to think about temporal and narrative organization. We have to create characters and stories in space and time in order to keep people’s attention. We’re not writing War and Peace, but narrative engagement is necessary so that people will watch the whole video.

SE: What do you enjoy most about being a Graphic Arts Director?

Stern: It’s exciting to get a new project, even just an illustration. It’s like, wow, here’s the mechanism this medical system works by. These days, there are hardly any new anatomical advances, so most illustrations show a molecular level. It’s also interesting to get projects that tell a story. In Interactive Medical Cases,7 we use case material and review article material to tell a story. We create characters that represent patients with medically true conditions. We need to include all the clinical information but also make it interesting. Plus, it’s always fun to draw pictures. I think that’s one reason why a lot of people in my department keep doing what they’re doing—they love to draw pictures.

SE: What are some of the challenges for your job or in your department?

Stern: One challenge involves the potential to go off into too many directions. There are many ongoing tasks, plus there’s always something new. Now we’re starting to work with filming and camerawork for video. A lot of people in my department are familiar with still photography, but what about video photography and lighting or spatial issues? We are constantly learning new things while at the same time handling the production requirements of a weekly journal. Every single day, there are still those italic periods to correct. The hardest part is coordinating the schedules, workflow, and production requirements with the creative and technical requirements that just keep evolving.

SE: These days, people have easy access to Photoshop and other graphic-editing programs. How do you deal with concerns about photo manipulation?

Stern: We have a protocol for trying to determine if images have been manipulated with Photoshop; we can see if something doesn’t fit the pattern. In the past, the changes people made were not so sophisticated; today it’s more complex. We do have to rely on authors’ probity.

There are also visual equivalents to the plagiarism-detection tools used for text. Sometimes we discover that others have plagiarized us. We might be looking at other websites for reference material and discover, hey, that’s our picture!

SE: Do you have any thoughts on where scientific publishing and editing are heading?

Stern: No, I’m only an illustrator <laugh>. Aside from issues around Open Source data, I think changes are probably going to be based on how social media is burgeoning and on how clinicians and patients use devices. It’s going to keep moving in the direction of more audio and video and maybe less text-only type. The COVID-19 pandemic may end up having a big effect on medical education; nowadays, people expect everything to be available online. I expect that more of publishing is going to be geared toward people looking at their cell phones or whatever device will replace their phones in the near future.

References and Links

- Lipton SA, Rosenberg PA. Excitatory amino acids as a final common pathway for neurologic disorders. N Engl J Med. 1992;330:613–622. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199403033300907

- Rosenthal N. Fine structure of a gene—DNA sequencing. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:589–591. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199503023320908

- Wells T, Donini C. Monoclonal antibodies for malaria. N Engl J Med. 2002;387:462–465. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2208131

- https://www.nejm.org/multimedia/videos-in-clinical-medicine

- https://www.nejm.org/multimedia/quick-take

- https://www.nejm.org/action/showPodcastsFeeds

- https://www.nejm.org/multimedia/interactive-medical-case

Elizabeth Bales is a Senior Manuscript Editor, New England Journal of Medicine, and Copyeditor, Science Editor.