Introduction

The transition to open access (OA) is accelerating. An ever-growing number of libraries and publishers are signing agreements that cover read access as well as OA publishing. The variety of OA models can get complicated quickly. One helpful distinction is whether the model is based on an article processing charge (APC) or not. APC-based models, like many versions of Read and Publish, have become the most commonly used by publishers seeking to transition to OA. But APCs have always had a potentially fatal equity issue baked into their core. Authors not covered by an agreement, and without means to pay APCs, cannot publish OA. They must rely on publisher managed waiver programs in order to make their work openly accessible. APC waiver programs, unfortunately, have not been successful at addressing the problem of author equity with Gold and Hybrid APCs. Now these same ineffective and problematic waiver programs are being assigned the even heavier lift of addressing the rapidly growing issue of author equity associated with the new APC-based OA models. That waiver programs are not up to the task of solving the author equity problem has not stopped APC-based models from being adopted by publishers at an accelerating rate. Evidence suggests this is not because publishers lack interest and concern for issues of equity and inclusion.

In 2017, 10 organizations that work in scholarly publishing founded a new collaboration to raise awareness about the lack of diversity and inclusion in scholarly communication. The mission of the new group, the Coalition for Diversity and Inclusion in Scholarly Publishing (C4DISC), is to “…build equity, inclusion, diversity, and accessibility in scholarly communications.”1 As part of its values, C4DISC member and partner organizations seek to welcome diverse perspectives, learn from different communities, make space for marginalized communities, and eliminate barriers. Among the C4DISC members or partners are the Council of Science Editors, Society for Scholarly Publishing, Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association, Elsevier, American Chemical Society, Sage, Taylor and Francis, and Wiley, as well as two of the authors’ own organizations, PLOS and the Iowa State University Library.

This article is about author equity and waivers, not about workplace diversity and equity, which is the focus C4DISC’s efforts to date. But we believe concern over waiver programs and author equity aligns squarely with the stated values of C4DISC and with many of the stated diversity, equity, and inclusion values of its member organizations. We also believe it is insufficient for scholarly communication organizations to only pursue equity and diversity in certain aspects of their operations while ignoring it in others. Therefore, this is an article about inequity in scholarly communication. It is about the continued restriction of space for marginalized communities in scholarly communication. And it is about the growth of barriers and the exclusion of diverse perspectives in scholarly communication.

The authors will offer 3 perspectives on the issue of waiver programs and author equity: 1) Romy Beard, until recently, was the Licensing Programme Manager at Electronic Information for Libraries (EIFL), where she worked with libraries and consortia from developing and transitioning economy countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa; 2) Sara Rouhi is the Director of Strategic Partnerships at PLOS, where she focuses on building non-APC, inclusive business models to make publishing more equitable; and 3) Curtis Brundy oversees collections and scholarly communications at the Iowa State University Library, which has committed to transitioning its subscription spending to support equitable OA. We will include recommendations for improving waiver programs as well as for adopting open models that have equity built in, making waivers unnecessary.

Before examining waivers from these 3 perspectives, we would like to foreground our views by looking at the distinction between equity and equality.

Equality vs. Equity as a Lens for Understanding the Waiver Issue

By Sara Rouhi

The scholarship on equity vs. equality is vast and not the focus of this particular paper. That said, it’s worth understanding the origins of this discourse in the context of early childhood education. Discussions unpacking the difference between these two concepts began to emanate from the early childhood education field in the early 2000s as researchers, teachers, and practitioners sought to understand the so-called “achievement gap” between Black and White students in American schools.2 This framework has since been used as a lens to understand everything from gaps in public health outcomes to income inequality.

In the following, my coauthors and I use the same lens to understand the inequities in the scholarly publishing system as constructed in the largely Western, White, English-speaking, high-income world3 to illustrate why waivers do not work.

At its core, the difference between equality and equity is about recognizing individual or group circumstances/differences and not assuming a level playing field. The Milken School of Public Health at George Washington University defines this distinction as follows:

Equality means each individual or group of people is given the same resources or opportunities. Equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.4

The social justice component to this distinction lies in the recognition that differences in circumstances are often systemic and, historically, often intentional. The post continues, “It’s critical to remember that social systems aren’t naturally inequitable—they’ve been intentionally designed to reward specific demographics for so long that the system’s outcomes may appear unintentional but are actually rooted discriminatory practices and beliefs” (emphasis added).

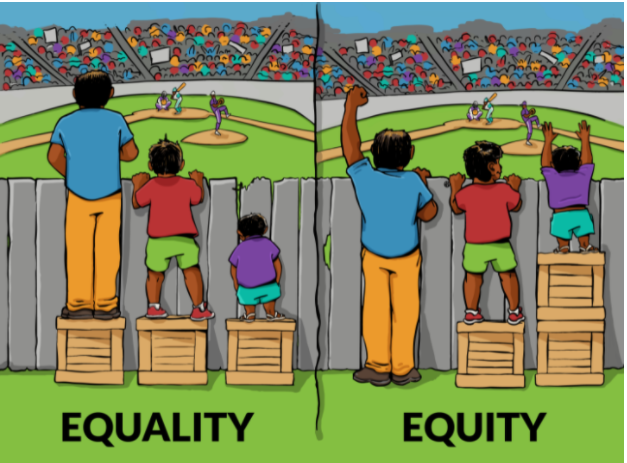

Over the years, artists have depicted this distinction visually to great effect. An illustration from Angus Maguire for the Interaction Institute for Social Change uses participation in the activity of watching a baseball game to articulate the difference (Figure 1).5

Giving everyone the same kind of “leg up” (via a booster box to stand on)—aka, “equality”—doesn’t take into account that the tallest viewer probably doesn’t need it, and the smallest viewer is not aided by it.

Taking an “equity-focused” approach that recognizes their relative circumstances (and the reasons behind them), changes our approach to solutions. Perhaps we don’t need to expend resources on the taller viewer; what we have available for the middle viewer is sufficient, but what we build for the shortest viewer needs to be enhanced. This more nuanced approach to facilitating opportunity is what the equality vs. equity distinction is about.

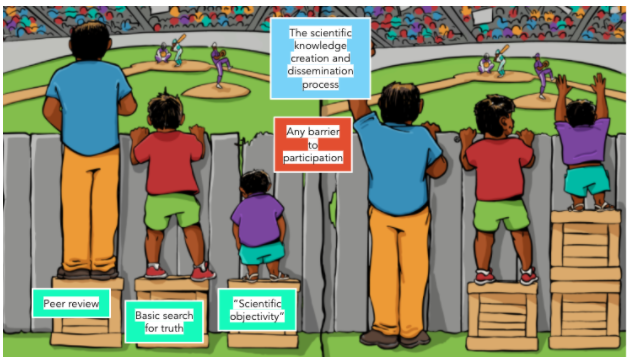

I have taken the liberty of augmenting Maguire’s image—as many on the internet have6—to bring this discussion into the scholarly communication space (Figure 2).

If we understand “the baseball game” as the practice of scholarly communication at large, the fence represents any/all barriers to participating in that ecosystem.7 Conventional wisdom says that things like double anonymous peer review and “scientific objectivity”—whatever that is—ensure that the system is equal and fair. “We’re all searching for ‘truth’ so, of course the system is fair.”

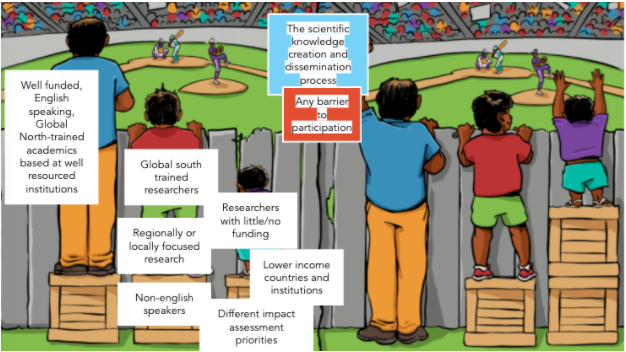

It is unsurprising that the establishment that built the system struggles to recognize that its structure and justification are systemically exclusionary. In Figure 2, the “scientific establishment”—or Western Research Industrial Complex—built the fence. They are bought into why it exists, they benefit from it, and they genuinely believe it makes science better, often without acknowledging its inequitable flaws (Figure 3).

These are the individuals who could comfortably see above the fence without any need for a booster box. The viewer who can just see and the viewer for whom the box does nothing represent the many thousands of researchers globally who try, in good faith, to participate in the “fair playing field” of academic research but can’t seem to ever get over the fence.

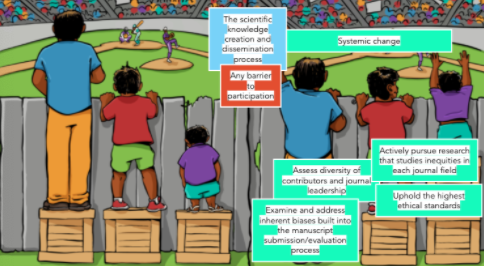

What each stakeholder community in scholarly communication must do—funders, researchers, research administrators, publishers, libraries, consortia, technology providers—is thoroughly scrutinize their systems to identify opportunities for essential systemic change, acknowledging the inequities they may be perpetuating via their own work. In the case of examples provided in Figure 4, I have highlighted public commitments PLOS has made to remain accountable to our equity work8 as examples of what this can look like for publishing stakeholders. Many other publishers are doing similar work and publicly sharing their commitments as well.

Waiver Issue From the Developing Countries’ Perspective

By Romy Beard

One of the issues with moving from a “pay to read” to a “pay to publish” model is that it creates a different financial barrier for authors from developing countries.9 Most universities, research institutions, and national research funding agencies from these countries do not have budgets to cover APCs, and authors have to pay from their own pockets. Many publishers recognize this, and have introduced a waiver or discount scheme for authors from lower income countries to allow them to publish their articles in OA without having to pay a full APC. Most publishers offer full waivers to authors from some countries, and a 50% discount to others.

However, there are a number of issues with these waiver and discount programs.

Firstly, the terms are not always fair: in some countries, discounts simply aren’t good enough, and the remaining APC is still too expensive. This was also found in a recent study undertaken by EIFL.10 The study, which analyzed the publishing output through 4 of EIFL’s OA agreements and found that OA publishing had increased by 62% from 2019 to 2020 and identified a number of articles that were published in closed access in 2020 despite being eligible for an APC discount. In some EIFL partner countries, researchers earn $400 a month, so paying a 50% discounted APC is still impossible. The fact that policies don’t always align with the realistic possibilities of authors in lower income countries was also made by the OA2020 Low-to-Middle Income Country (LMIC) working group,11 which contacted authors in 4 countries to enquire about their APC payments. One researcher wrote: “We received a full waiver after we explained that we did not have funds available for the Article Processing Charges, and that the charges were higher than the monthly wages of some lecturers in Ghana.”

Secondly, waiver and discount programs are poorly communicated, and many authors are simply not aware of them. The information on publisher’s websites is not always clear; statements are often general and not linked to specific title lists, and there is no or little information on individual journals’ websites. There isn’t a single place where authors can search across journals from different publishers and see which journals might offer them an APC waiver or discount. Being aware of this might encourage them to submit their article to certain journals that offer waivers or discounts rather than closed subscription journals. The fact that the ability to pay an APC influences researcher’s publishing decisions is also echoed by the OA2020 LMIC study: one respondent wrote that they “didn’t pay any charges, [but] got a waiver. In fact, if they didn’t waive the charges, we would have published it elsewhere.” Many others echoed this statement.

Thirdly, waivers and discounts are not automatically applied. In many cases, authors need to know that they are eligible for a waiver; they might need to tick a box during submission, or even send an email to actively request the waiver or discount. One publisher’s website12 is covered by a large heading entitled “Automatic Waivers,” which is then followed by the small print, “Automatic waivers will only be applied if the corresponding author requests a waiver at the payment step during the article submission.” That is not an automatic waiver. The EIFL study also found that some articles were published in closed access despite being eligible for a full APC waiver because the publisher in question didn’t have automatic recognition in place—authors needed to email the editor to claim the waiver. The need to “claim” a waiver complicates the process for authors and acts as a hurdle to OA. As one of the OA2020 LMIC respondents states, it makes the whole waiver process “a painful task.” This is an additional burden put on unfunded researchers.

A fourth issue is that terms can change unexpectedly as publishers move countries from the waiver to the discount category without notice. Many authors from the OA2020 LMIC study—which spanned 3 years—found themselves eligible for waivers in 1 year, but only received a discount in the next year. Consequently, they continued to only submit their papers to journals where they knew they would receive a full waiver. Once again, we see that the author’s decisions about where to publish their articles are influenced by their ability to pay APCs.

Finally, hybrid journals are usually excluded from publishers’ waiver and discount programs. The argument behind this is that for those journals, authors can always choose not to pay the APC; however, this doesn’t make OA publishing equitable—in fact, it pushes authors to publish behind the paywall in those journals. To make OA truly equitable, hybrid journals should be included in these programs.

What can be done to address these issues? Here are some suggestions for publishers to improve APC waiver and discount programs and make them more equitable:

- Publishers should research realistic local funding opportunities before deciding which countries fall in the waiver or discount group.

- Publishers should have clear presubmission information on waivers and discounts for authors. This might include a general page with a downloadable title list of eligible journals (ideally this should include subject information and journal metrics), information on each journal’s web page, and clear information during the submission process.

- Workflows that allow for automatic recognition of eligible authors during the submission and postacceptance process—those publishers that do not currently allow this need to move fast.

- Publishers should also make it clear how long the terms on the offer are valid and when they might be updated.

At the same time, the question arises about whether APC waiver and discount models are effective for authors in lower income countries. Should authors from these countries even “see” an APC price tag? Perhaps authors could be offered free publishing through agreements like free Read & Publish that EIFL has signed on behalf of its partner countries with some publishers. Or are there other, alternative models that can solve the issues raised and make the process smoother?

Waiver Issue From the Publisher Perspective

By Sara Rouhi

To understand the challenges with waivers, it is vital to understand the assumptions publishers like PLOS made when launching the APC model. It is also important to keep in mind the differences in equity vs. equality, as previously outlined, when discussing issues of inclusion.

With respect to assumptions PLOS (and indeed all APC innovators at the time) made: at the time, in the biomedical space, charging authors fees to publish seemed fair and reasonable. Those authors were awarded huge grants and if a nominal fee meant that anyone could read and (appropriately) reuse the paper, it was a price worth paying.

Unfortunately, embedded in that thinking were “unknowns” that the scholarly publishing community didn’t predict:

- We didn’t anticipate how popular and successful APCs would be as a business model.

- We didn’t appreciate that the pressure to publish, coupled with inexperienced authors and a new business model, would yield predatory publishers. Their efforts would greatly undermine the credibility of OA publishing for many years.

- We didn’t appreciate how much money was in the publishing ecosystem. With costs of publishing shifting to authors, libraries were still seeing exploding subscription fees for the same content their authors were paying to make open. Commercial and nonprofit publishers alike developed multiple revenue streams around the same content.

- We overestimated the ability of waivers to address inclusion and equity.

As Gold OA has taken hold as the dominant model in OA publishing, the inequities built into the model have exploded exponentially, shutting out large communities. Early career researchers, those in fields with no funding, and those based in low and middle income countries cannot afford to publish openly using this model. They rely on subscription publishers who charge reading fees to peer review and publish their research, often making their research inaccessible to their own communities.

Why Waivers Do Not Meet the Open Access, Open Science Moment

The reason publishers and other scholarly communications stakeholders (like libraries) need to examine and (ultimately, I argue) reject waivers as a vehicle for inclusion in publishing is that they fail to meet the equity standard.

Simply put, they do not address the systemic structures that lead authors to need waivers, and, as Beard outlines above in depth, waivers themselves are structured to ask those most in need of systemic change to jump through hoops that more privileged communities never see.

If waivers are meant to solve the problem of “APCs-as-a-barrier-to-participation” we must examine more deeply: Why are APCs such a dominant business model?13

The short answer to the first question is simple: for publishers, it is the easiest and most effective business model to make content OA.14 Like any other “retail” sale, the “consumer” pays a one-time fee for a one-off service. In this case, the consumer is the author and she pays an APC upon article acceptance for the services of manuscript handling, peer-review management and facilitation, online dissemination, marketing/communications, and indexing of her work.15

For funders, it is the easiest way to disseminate publishing fees. Rather than radically restructuring how they support publication fees to ensure compliance with OA mandates, funders just incorporate publishing fees into the grants for which researchers apply.16

For libraries (mostly in Europe) that are reacting to funder mandates, their entire administrative infrastructure to support OA publishing (and now transformative agreements) is based on only one business model—APCs. As more publishers come into the marketplace with non-APC–based models, libraries and consortia are struggling to “turn the aircraft carrier” in the direction of more inclusive models.

So, for the progenitors of the Western Research Industrial Complex, APCs are a simple model that works for their well-funded researchers and institutions. These stakeholders argue: waivers are a simple, relatively inexpensive way to address the outliers who exist within their system.

But what about everyone else?

As Beard notes above, whether or not waivers ever functioned as they were originally intended, they absolutely do not now. Even for Western, English-speaking, US dollar publishers, waivers do not work anymore.

Publishers and the Unsustainability of Waivers in a Global Open Science Ecosystem

Simply put, there are three major reasons that waivers no longer “work” to address the barrier of publishing charges: the complexity of digital publishing workflows, the explosion in demand for support, and inadequacy of a “needs based” medium to build a community of inclusion.

Workflows. As publishing has gone digital and the entire submission, peer-review, and dissemination process has moved online, the technologies and know-how required to undergird them have become infinitely complex. Publishers have had to either become technology companies or pivot to integrate third party technologies—either route being complicated and expensive. Determining the technology workflows to support waivers implicates not just the manuscript handling process but also accounting, editorial operations, and customer support workflows.

As Beard notes above, the communications around how waivers work are obscure, obtuse, and often frustrating for authors. At PLOS, as of January 2022, we currently have 2 mechanisms for fee support,17 one based on geographic location of the authors’ funders and the other based on need, the PLOS Publishing Fee Assistance (PFA). Because of how our editorial submission system, Editorial Manager (a third party platform run by Aries, now owned by Elsevier), is built, as well as our accounting requirements as an annually audited nonprofit, authors must go through a lengthy process to “prove” they have no other source of funding for their publication fees, despite the fact they are only just submitting. This is even as 50% of authors (in the case of PLOS ONE’s acceptance rate) will not ever be accepted for publication.

Once an author has successfully documented why they need fee assistance, internal teams within publishing and accounting have to evaluate the criteria they use for determining the amount of assistance PLOS can provide while ensuring that PLOS practices are audit-compliant and as consistent as possible. Accounting, particularly, hits snags when authors who had funds at submission cannot pay at acceptance. Those authors have little recourse other than to renege on their commitment to pay the APC, an unacceptable outcome for any organization committed to sustainable business practices.

PLOS is currently evaluating and completely overhauling our waiver system so we can continue to shed more light on our decision and best practices around this work and hope to share more of that work in 2022 and beyond.

Demand. Additionally, as awareness of OA has increased and open science has become the focus du jour (especially post-pandemic), the explosion in demand for waivers has made them very expensive. At the height of its waiver expenditures, PLOS was spending upwards of $3,000,000 annually to grant full and partial waivers to authors who could demonstrate need. As PLOS shifts to focus on underrepresented communities and regions, we have increasingly moved our waiver focus to geographies where partial waivers are insufficient. Many researchers often cannot afford any amount of discount on publishing fees—publishing has to be free.

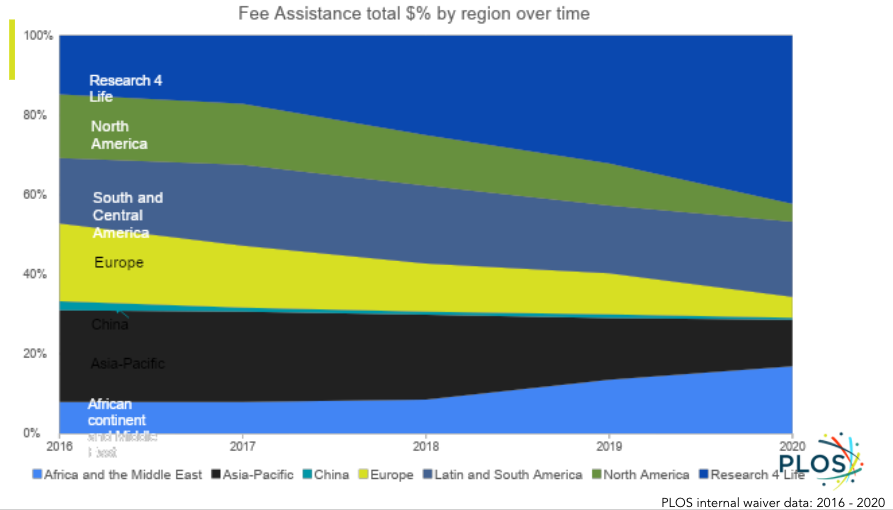

Figure 5 represents the reduction in total waiver spending alongside the shift to underrepresented regions who need higher dollar support per paper. PLOS’s decision to reduce total spending on waivers overall is the result of a shifting publishing landscape that has reduced PLOS’s publishing revenues (from their peak in 2012–2015) and a commitment to more inclusive models that do not require authors to pay any fees.18 PLOS’s current work to reduce its own internal costs and regain market share via more equitable models should hopefully begin to reduce the need for a large waiver expenditure.

Also indicated in Figure 5 is the reality that Research 4 Life countries, countries on the African continent, and Latin America are seeing increased waiver support (despite the overall reduction in waivers spent) while PLOS reduces support in higher income regions. This is far from a perfect solution to address the near-term adjustments required to transition to more equitable models. PLOS is the first to call out that the geographic inequities we are trying to address in this adjustment do not meet the needs of researchers in higher income countries who legitimately cannot pay APCs (Figure 6).

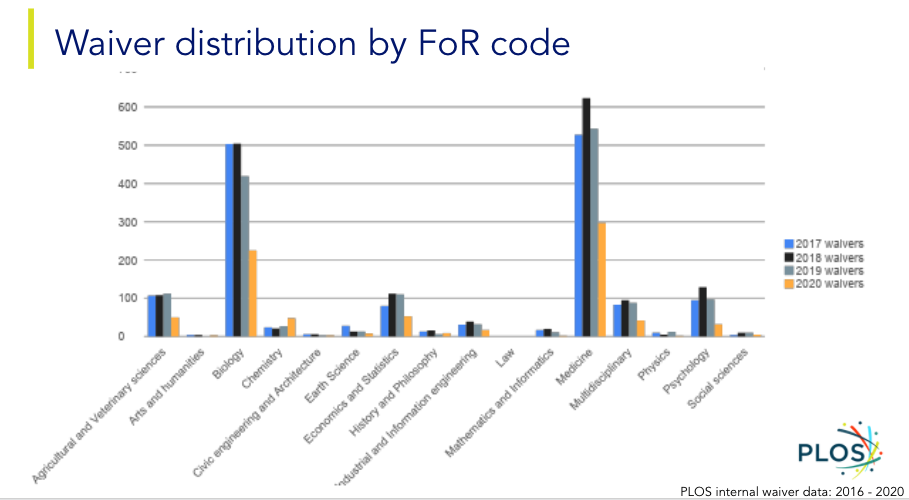

Many researchers who urgently want their work to be OA and available to broader practitioner communities have no funding sources to pay publishing fees. This is true whether or not you’re in a well-funded region or institution. Other researchers are still early in their careers and have not yet secured large grants to fund publishing fees. Academic libraries, departments, and administrators trying to support these researchers almost never have enough money to meet the demand for APC funding support. Figure 6 demonstrates how the need for full funded waivers (not just discounts on the APC fee) is ultimately a reduction in the total number of waivers you can provide. 2020 is the best example of that result.

Inclusion. Lastly, there is nothing about “demonstrating need” that is “designed for dignity,” a term my colleague and friend, Dr Kamran Naim, Head of Open Science at CERN, refers to when speaking about equity in research. The effect of asking for a handout in a process that is already built on peer critique and (often) community rejection assumes unfunded authors are “out for what they can get.” Many “needs based” efforts are built on an assumption often made of lower-income communities in other contexts that is based in racial prejudice—remember 1980s “Welfare Queens”?19

What Can publishers Do to Address These Issues?

No discussion of what publishers can and should do to address this issue can exist outside of the context of recognizing the interconnectedness of the scholarly communications ecosystem and the role of all stakeholders to engage with this issue. Bringing equity to scholarly communications requires a cross functional approach that involves funders, research institutions, individual researchers, libraries, service providers, and publishers. No one group is going to solve this themselves.

That said, publishers can and must examine new paths to ensure access to publishing and peer-review services is as available to authors as OA articles are to readers. An inclusive publishing ecosystem makes reading and publishing completely open, eliminating fees for individuals wishing to participate in those aspects of the scholarly communications process. There are band-aid short term solutions and longer term efforts we must all examine.

For publishers like PLOS that still rely on waivers, we must:

1. Reexamine our waiver programs from start to finish and identify where we are creating unnecessary, burdensome hurdles for researchers. For most publishers, waivers are not the first workflow they are working to optimize. But if waivers are going to remain the near term mechanism to facilitate inclusion in APC publishing models, publishers must reexamine the entire process to identify ways to make it more transparent, accessible, and light-touch. In her section above, Beard has identified many areas where all publishers can improve.

2. Beyond just optimizing current workflows, publishers should transparently share their plans and strategies around increasing participation in APC publishing models via waivers. If publishers insist that APCs are their preferred business model to facilitate the “flip” to an OA paradigm, they must present a comprehensive strategy explaining how this will work. What are the communities they wish to target? How are they going to communicate the waiver options to those communities? What organizations are they partnering with to facilitate this (like EIFL or Research 4 Life)? What are their metrics for success and how are they going to measure progress?

The strategies around building inclusion through waivers should be as robust and transparent as those aimed at authors who can pay full fees. If publishers’ commitments to diversity, equity, and inclusion are truly substantive, this is an essential part of that work.

3. Publishers should consider business models and partnerships that eliminate the need for waivers. This is, no doubt, a heavier lift. PLOS has spent over 2 years focusing its efforts here in the hopes to eliminate the need for waivers in the long term. Many publishers are experimenting with innovative new models that flip paywalled content to make it OA, but fewer are pushing models that shift fees away from authors entirely.20 As demonstrated by PLOS,21 these models can work successfully, but they often require the publisher to engage in price transparency work22 (as recommended by Plan S) and to reduce expectations around revenue maximization.23

4. Publishers must work collaboratively with libraries, library consortia, and funders to rethink the existing workflows that lock funder publishing fee support into individual grant funds with no mechanism for allocating those funds centrally. Libraries urgently want to support OA publishing efforts that shift fees away from authors (as Brundy outlines below). The current transition period of shifting subscription spending to cover publishing fees in the context of “transformative agreements” enables future OA publishing with existing collection development budgets. Jumping to support native OA publishers (with whom they’ve never had subscriptions) or models based on collective action (where they have no allocated budget) means that libraries are searching for new money in a budget landscape decimated by further pandemic-related cuts.

While their researchers are indeed spending to publish OA, often that money sits in individual grant funds and is not accessible in a centralized way. Ideally, in the future, most libraries will manage OA publishing budgets (as they currently do in the UK and much of Northern Europe) once subscriptions are a thing of the past. In the near term, funding is still locked within individual grants.24

As in any paradigm shift, the work can seem overwhelming, but small iterative efforts can pay off, and publishers that engage in good faith with this work see strong support from libraries, consortia, and funders. PLOS remains committed to supporting other publishers in any way we can to share what’s working and what’s failing so that others can advance from the work we have started and hopefully reduce effort duplication.

Waiver Issue From the Institutional Perspective

By Curtis Brundy

The Iowa State University Library is a signatory of OA202025 and, with unanimous support from our Faculty Senate, adopted new journal negotiation principles26 in 2019. The principles prioritize openness and transparency and state that we will “work toward democratizing access to knowledge by reducing financial barriers inherent in traditional publishing practices.” In 2021, the library’s OA agreements allowed nearly 20% of Iowa State’s corresponding authored articles to be published openly.

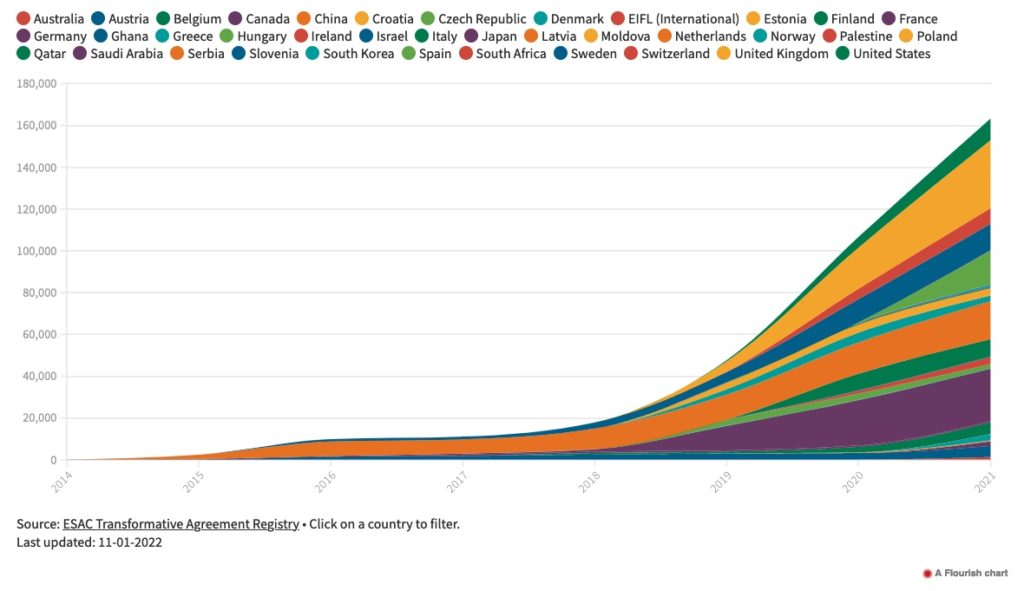

Iowa State has pursued an OA strategy that includes agreements utilizing APC-based and non-APC–based models. Several of our OA agreements have resulted from close partnerships with publishers on the development and implementation of new open models. In the last few years, this type of close collaboration27 between libraries and publishers has had a significant impact on the number of articles published OA. The ESAC Initiative has provided a dramatic visualization of this growth, based on the OA agreements added to the ESAC Registry (Figure 7).

Adoption of OA agreements in the United States still trails that in Europe, but the pace, particularly for those built on APC-based models, is accelerating. Cambridge University Press has signed over 250 read and publish agreements with US libraries.28

As APC-based models such as Read and Publish have achieved wider adoption by publishers and greater traction with libraries, we have become disappointed by the lack of attention and progress towards improving author equity. Publishers have been quick to innovate in many critical areas as they seek to meet library interest in supporting OA: new OA platforms and workflows have been developed and implemented, exciting collaborations are taking place on joint infrastructure projects like the OA Switchboard, and targeted acquisitions to build capacity and fill gaps are announced by publishers with regularity. But to date, little-to-no energy and enthusiasm has been applied to addressing the author equity issue at the heart of APC-based models. The near universal response has been to point to existing APC waiver programs when questions of author equity arise. As my coauthors have already pointed out, however, existing waiver programs are completely inadequate for the task.

The Iowa State University Library remains committed to an equitable transition to OA and believes a diversity of open approaches will be necessary. In the short term, this will include APC-based models, which we will continue to adopt as part of our overall strategy. But we are actively working to raise awareness about waiver program issues and advocating for reform. Here are a few suggestions for how libraries can help ensure author equity during the transition to OA:

- Pursue non-APC–based OA agreements that have author equity built in, such as Subscribe to Open, Association for Computing Machinery’s Tiered Open, and collective models such as Open Library of Humanities and those being adopted by PLOS.

- When making an APC-based agreement, address the issue of author equity and waivers directly by adding license language that commits publishers to fully and transparently working on the issue of author equity by implementing waiver program improvements.

- Continue to collaborate with publishers to iterate, develop, and adopt equitable open models.

- Support and lead inclusive national and international efforts to improve author equity.

Conclusion

We know that the transition to OA is happening, and that thousands of articles that would have previously been behind the paywall are now published in OA due to agreements such as Read and Publish. But how many articles are being published in OA by unfunded authors from lower income countries via waivers and discounts? How many are not being published in OA, and pushed to publish behind the paywall, globally?

Publishers have set up waiver and discount programs, are improving how their systems recognize authors, and are addressing some of the issues raised in this article—but is enough being done? Stakeholders across the publishing ecosystem have to ask themselves serious questions about how they wish to engage in this paradigm shift. Do publishers want to rely solely on waivers to facilitate inclusion? Do libraries want to spend funds supporting publishers lacking a specific inclusion strategy? To what extent is signing Read and Publish agreements en masse just further propagating models no longer appropriate for our current open science goals?

Organizations like EIFL, PLOS, and the Iowa State University Library are loudly asserting a position on these difficult questions and we, the authors, feel that we can collectively put more pressure on our respective communities to bring transparency to their answers around these questions.

While we hope that this article has offered some solutions, there still remain many unanswered questions that need to be discussed within the scholarly communications environment in order to agree on a more coordinated approach. The most important point is that these discussions should not be had without involving those concerned—libraries and authors from the lower income countries in question.

References and Notes

- https://c4disc.org/

- Richard Milner provides a comprehensive overview of the questions in the following article: Milner HR. Beyond a test score: explaining opportunity gaps in educational practice. J Black Stud. 2012;43:693–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934712442539.

- Elsewhere, I refer to this complex of stakeholders as the “Western research industrial complex.” See Rouhi S. When metrics and politics collide: reflections on peer review, the JIF and our current political moment. Scholarly Kitchen. 2017. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/09/18/guest-post-metrics-politics-collide-reflections-peer-review-jif-current-political-moment/.

- Equity vs. equality: what’s the difference? MPH@GW, the George Washington University online Master of Public Health program. 2020. https://onlinepublichealth.gwu.edu/resources/equity-vs-equality/.

- Image and background of its development available at https://interactioninstitute.org/illustrating-equality-vs-equity/ with CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

- The Evolution of an Accidental Meme. https://medium.com/@CRA1G/the-evolution-of-an-accidental-meme-ddc4e139e0e4#.pqiclk8pl.

- These are, incidentally, the very barriers that the Open Science movement is actively working to undermine. See the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science adopted in 2021 at https://en.unesco.org/science-sustainable-future/open-science/recommendation.

- Heber S. Our commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. The Official PLOS Blog. 2020. https://theplosblog.plos.org/2020/07/our-commitment-to-diversity-equity-and-inclusion/.

- The research on this is fairly conclusive. See Smith AC, Merz L, Borden JB, et al. Assessing the effect of article processing charges on the geographic diversity of authors using Elsevier’s “Mirror Journal” system. Quant Sci Studies. 2022;2:1123–1143. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00157.

- https://eifl.net/blogs/eifl-agreements-result-increased-oa-publishing

- See https://oa2020.org/oa2020-lmic-project-brief/.

- The publisher in question is Wiley. See https://authorservices.wiley.com/open-research/open-access/for-authors/waivers-and-discounts.html.

- Related to this is the question of if Gold OA is the only mechanism for facilitating the current “transition to an OA world.” That is a lengthier discussion for which there is no room in this piece. That said, it is important to acknowledge of course that Green OA and Diamond/Platinum OA are other vehicles for inclusion. They are just not nearly as dominant as the Gold OA—author-pays—business model.

- It has also facilitated the practice of “double dipping” whereby subscription publishers charge libraries reading fees and then also charge authors publishing fees to make their content open—effectively generating two different revenue streams pulled from two different funding sources (libraries vs. funders) for the same piece of content.

- There are other models looking at covering the costs of rejected papers by charging at submission rather than article acceptance, but these are nascent and there is little consensus on their long term viability.

- Note: From the publisher and library perspectives, the challenge of publishing funding that is “locked away” in individual researcher grants is one of the biggest obstacles to support more equitable, inclusive OA publishing models like those pioneered by Annual Reviews, MIT Press, and PLOS.

- A complete overview of PLOS fees and assistance programs is here: https://plos.org/publish/fees/.

- See more about PLOS’s non-APC–based business models for unlimited publishing Flat Fees, Community Action Publishing and Global Equity here: https://plos.org/resources/for-institutions/how-can-we-partner/.

- For more on how Ronald Reagan propagated the racist idea of “Welfare Queens” during his 1976 presidential campaign, see NPR’s “The Truth behind the Lies of the Original ‘Welfare Queen’,” December 20, 2013: https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/12/20/255819681/the-truth-behind-the-lies-of-the-original-welfare-queen.

- Exceptions to this include Open Library of the Humanities, Knowledge Unlatched, Annual Reviews, and the many other publishers that have adopted the Subscribe 2 Open model. Additionally, as Curtis Brundy outlines in his section, many libraries are pioneering models to facilitate eliminating author fees. See the work of Community-led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs and LYRASIS’ Open Access Community Investment Program.

- In 2021, PLOS’s work in new, non-APC–based business models was recognized by the Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers’ Innovation in Publishing award (shared with Coherent Digital and their Mindscape Commons VR work). That award was in recognition of the fact that PLOS’s Community Action Publishing (CAP) model is actually generating more revenue than when PLOS relied on APCs and is aimed at cost recovery rather than revenue maximization. Learn more here: https://theplosblog.plos.org/2021/09/plos-wins-innovation-in-publishing-award/ and https://www.alpsp.org/news/winners-announced-alpsp-awards-september-2021/275591.

- Plan S issued their Price Transparency Framework in 2020 and PLOS, Company of Biologists, and F1000 Research have all publicly shared their frameworks in compliance with Plan S recommendations. See https://www.coalition-s.org/price-and-service-transparency-frameworks/ and https://theplosblog.plos.org/2021/09/our-commitment-to-price-transparency/.

- PLOS CAP actually shares a public revenue target that includes a cost target and a 10% margin. Once these targets are met, PLOS contractually commits to redistribute additional revenues above the target to community members of each journal. Details and targets are here: https://plos.org/resources/community-action-publishing/.

- Funders and other #scholcomm stakeholders are beginning to have these conversations. In Fall 2021, Plan S did a retrospective on their Society Publishers Accelerating Open Access and Plan S work (in which PLOS and many other publishers participated) and issued an independent report calling for exactly this kind of cross-stakeholder alignment. See https://www.coalition-s.org/open-access-agreements-with-smaller-publishers-require-active-cross-stakeholder-alignment-report-says/.

- https://oa2020.org/mission/#eois

- https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cos_reports/1/

- An example of this type of collaboration is the work between 4 leading US university libraries and the Association for Computing Machinery: https://www.acm.org/media-center/2020/january/acm-open.

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/open-access-policies/read-and-publish-agreements/americas

Sara Rouhi (0000-003-1803-6186) is Director of Strategic Partnerships at PLOS. Romy Beard (0000-0002-1064-4366) is Publishing Consultant with Romy Beard Consultancy. Curtis Brundy (0000-0003-3681-675X) is Associate University Librarian for Scholarly Communications and Collections at Iowa State University Library.

Opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the Council of Science Editors or the Editorial Board of Science Editor.